Canadian Mennonite

Volume 14, No. 17

Sept. 6, 2010

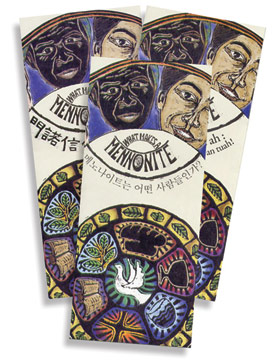

Three views of our ‘multicultural’ church

April Yamasaki writes of how her congregation in Abbotsford, B.C., has been deliberate in its embrace of ‘mak[ing] disciples of all nations.’ Samson Lo explains the goal of Mennonite Church Canada’s Multicultural Ministry and the biblical basis of ‘one church, many peoples.’ In our final piece, Joon-hyoung Park challenges the church to go beyond ‘just sharing a space with other ethnic groups’ if it wants to avoid the appearance of ‘just a landlord’s temporal charity.’

Becoming a multicultural church

|

In 1981, the newly formed Emmanuel Mennonite Church drew on Jesus’ words in Matthew 28:19 to express its purpose as a congregation: “To make disciples of all nations.” At the time, the intention was simply to begin an English-speaking church, but, in the years since, it seems to me that those words have proven to be more prophetic than anyone might have realized at the time.

In almost three decades, Emmanuel’s original membership has grown to more than 270, as the predomi-nantly Russian Mennonite group has been joined by people from “all nations,” including Germany, Holland, Vietnam, China, Japan, El Salvador, Kenya and Iran.

Emmanuel might not be officially “multicultural,” according to the standard definition of having a minority of at least 20 percent, but there are enough visible minorities that visitors often remark on it.

At Easter, the traditional greeting, “Christ is risen!” was given in a number of different languages. At our Peace Vespers last November, we deliberately included prayers in English, German, Portuguese, Farsi, Arabic, Japanese, Swahili and Halq’eméylem.

In a recent sermon, I noted that “community is the work of God in our lives. It’s not something that we can accomplish on our own. It’s God who transforms us.” So none of us can take credit for the growth and change in the church over the years.

Yet humanly speaking, I also believe that there are a number of key dynamics that have had an important role:

• Risk-taking: I realize that Emmanuel took a huge risk in calling me as a pastor 17 years ago. The church had wanted a pastor with previous experience; I had none. The church had wanted a pastor trained in an Anabaptist-Mennonite school; my degree was from an inter-denominational school. Some weren’t sure whether to be more surprised that the church was calling a woman pastor or someone who—in their minds at least—“just wasn’t Mennonite.”

Still, the church took the risk, and so did I. And it’s that same kind of risk-taking and openness to change that is necessary if we are to become more multicultural and accept the challenge of opening the doors of the church and the doors of our hearts to others.

• Empathy: Years ago, when we were both in our 30s, a friend visited a church where she was the only “white” person. “It was the first time I felt like a minority,” she said to me. How strange, I thought, that it took her that many years to feel that kind of difference!

I empathize with those who are minorities in the church, who are not sure that they can—or even want to—“become Mennonite,” or who feel frustrated as permanent outsiders to the in-group who all seem to be related.

I also empathize with those who find change difficult, who may even feel that they are losing “their” church. Both need to hear that together we can become more than we are, that we can become more and more the people that God is calling us to be.

• Being deliberate: It takes effort to talk to the stranger in the church foyer instead of focusing only on those we already know and love. It takes time to get to know and include the gifts of others—not in a token way, but in a real way that makes a difference.

In gatherings for prayer, I let people know that they can pray in the language they prefer. In worship, we sometimes sing songs in a language other than English, or encourage people to sing in the language they prefer. As I write this, though, I realize how little we actually do these things and I pray for more deliberate action.

• Vision: To be—or become—a multicultural church, we need a vision for the church that is bigger than those who are already part of the church, a vision that moves us beyond ourselves and our own circles. In that way, the original founders of Emmanuel certainly got it right: We need to make disciples of all nations.

We still have a lot to learn, and often stumble on the way. But by God’s grace, that vision is still before us.

One church, many peoples

|

I travelled throughout Europe in the early 1980s. I had the opportunity to come across some Mennonites and learn something about Anabaptist history and teaching, preparing me for God’s leading to Vancouver, B.C., in the late ’90s, where I began serving with Chinese Grace Mennonite Church. In this capacity I was then elected to serve for six years on the Committee of Church Ministries for Mennonite Church British Columbia.

Inspired by the recommendations of Hugo Neufeld’s report, “The Diversity Project,” MC Canada took on the biblical mandate of striving to maintain good, harmonious relationships between all people and between people and their Creator. In 2002, MC Canada offered me the position of director of multicultural ministry. Since then, I have often been asked what this ministry is all about.

When God created the first human beings in God’s image, the Bible tells us that “God saw that it was very good.” It was God’s intention that there be good, harmonious relationships between all people, and between people and their Creator. But sin destroyed that ideal state, which finally culminated in the Tower of Babel, where multi-ethnicity started.

Throughout the Old Testament, there were prophetic voices that called for a move towards reclaiming that “goodness” and being reunited with God and with people, such as in Psalm 100: 1, where “all the Earth” is to “make a joyful noise to the Lord.”

With the coming of Jesus we have a renewed call to all people “that they may all be one” (John 17). With Christ’s death on the cross and his resurrection, the way was paved for reconciliation with God and with one another.

At Pentecost we saw the early church coming together in over a dozen different nationalities and languages. After that, the church branched out “to all the world,” as called for by the Great Commission in Matthew 28:16-20.

Finally, Revelation 7: 9-10 prophesizes a beautiful picture of things to be, where “a great multitude that no one could count, from every nation, from all tribes and peoples and languages, [stood] before the throne before the Lamb, robed in white, with palm branches in their hands. They cried out in a loud voice, saying: ‘Salvation belongs to our God who is seated on the throne, and to the Lamb!’?”

Ever since I came to Canada I have heard and seen so much of how “Canada is a rainbow of colours,” with people from numerous different cultures, such that it has become a microcosm of the world’s ethnic, religious, linguistic and racial diversity. As former prime minister Jean Chretien put it: “It contains the globe within its borders.” Indeed, we have the world coming to us. What an opportu-nity! What a privilege!

The objective of this Multicultural Ministry office is “to work towards integration of people groups within Mennonite congregations, and cooperation among people of different ethnic, social, national, political and religious backgrounds.” In short, we want to build bridges to ethnic groups, be attentive to their needs and make sure that they are better served by MC Canada programs and better represented in denominational leadership.

The office of Multicultural Ministry has an important mission, and it takes a concerted effort to bring everyone together. Besides diversity in culture, language, tradition, practice and custom, there are also geographical restrictions, as our multicultural congregations are so widely dispersed in different major cities across the country.

How do we bring them together, both physically and in spirit? How do we break down the tangible and intangible barriers between different groups? How do we learn from one another and learn to appreciate one another? I would like to leave these and many more questions with us as food for thought.

Essentials for building a multicultural church

|

According to research conducted by sociologists Curtiss Paul Deyoung, Michael O. Emerson, George Yancey and Karen Chai Kim, 92.5 percent of Catholic and Protestant churches throughout the U.S. can be classified as “monoracial.” This term describes a church in which 80 percent or more of the individuals who attend are of the same ethnicity or race. The remaining churches—just 7.5 percent—can be described as multiracial.

The majority of churches, whether or not they appear seriously multicultural, still fall behind in embracing the true meaning of multiculturalism and applying it practically among their members. In their minds they may believe that the 21st century is an era of “acceptance” and “adaptation,” but they do not know how to practically react to new multicultural surroundings and how to warm-heartedly welcome people of different cultures. Instead, they easily hunker down, defending uniformity and resisting diversity.

Surely, it must break the heart of God to see so many Christians and churches throughout this country segregated and detached racially and culturally from one another, and that little has changed since it was first observed that 11 o’clock on Sunday morning is the most segregated hour in North America.

In an increasingly connected—yet stubbornly sectarian Mennonite world—it is time to recognize that there is no greater tool for becoming a missional, multicultural church than the witness of diverse believers walking, working and worshipping God together as one in and through the local church.

The pitfall of multicultural awareness

A few multicultural churches among Canadian Mennonites have recently been seemingly aware of embracing all nations under one roof. They may listen to their cultural demands on the style of worship, communion—and other trivial practices—only as far as it does not affect the church’s direction and growth. Going through tough and subtle turbulences stemming from their cultural concoctions, they only learn to be patient and persevering, and do not tackle the challenge of resolving and reconciling in faith.

Mennonite churches, as a whole, as they stubbornly or conventionally stick to their own principles and practices, can be categorized as practitioners of low-level multicultural awareness. Both denial and defence are typical icons for them. Soon they jump up to the next stage of self-complacence, declaring, “We are okay now.”

Intentionality needed to create a multicultural church

To create a harmonious mixture from different-coloured ingredients requires a fundamental premise among leaders and lay people: intentionality. A multicultural church does not just happen. Everyone engaging in ministry must first identify and then take intentional steps to turn their vision into reality.

As multicultural minister and author David A. Anderson emphasizes in his book Multicultural Ministry, “intentionality is absolutely critical” to the success of multicultural ministry. Just as Jesus placed himself in an environment where he would have social contact with non-Jewish people, like the Samaritan woman, we should also recognize that intentionality is the key premise of evangelizing people.

I have no doubt that people in many, if not most, homogeneous Mennonite churches would sincerely state that they would not intentionally turn anyone away. If asked, they might say something like, “We welcome anyone to become a part of our church,” or point to the fact that “a few families” of diverse ethnicity do attend their otherwise homogeneous fellowship.

In fact, some pastors have specifically stated, “We would love to have more diverse individuals in our church as long as they like our music, our preaching style, and our spirit. But they should not expect us to change for them.”

These well-meaning homogeneous people are not doing anything intentionally to turn diverse others away. However, they are not doing anything to draw them in either. And this is, to be honest, exactly the impression I received when I first joined a Mennonite church in 2004, and the observation remains unchanged since then.

Without any sacrificial intentionality, it is useless to build a multicultural church. Note that just sharing a church space with other ethnic groups—or renting space out to them—is not a multicultural ministry; it is just a landlord’s temporal charity.

Who are our multicultural Mennonites?

|

Once upon a time, Mennonite congregations in Canada could largely define themselves by German or Swiss Mennonite heri-

tage, but no more. Mennonite Church Canada congregations now represent an increasing variety of cultural and ethnic backgrounds; currently, 49 of them worship in 19 languages other than English or German, including Amharic (Ethiopian and Eritrean), Cantonese, Chin, Hmong, Japanese, Karan, Korean, Laotian, Mandarin, Spanish, Tamil, Thai and Vietnamese.

As the tapestry of MC Canada grows more diverse, it has increased opportunities to learn about Christians from around the world, strengthening the denomination’s relationship with the global Mennonite church. Spanish-speaking congregations, including First Mennonite Church, Kitchener, Ont.; First United Spanish Mennonite Church, Vancouver, B.C.; and Iglesia Nueva Vida in Toronto, Ont., relate to Iglesia Menonita Hispana, the North American conference of Spanish-speaking Mennonites. Lao, Vietnamese and Korean congregations also belong to North American bodies.

According to Samson Lo, director of Multicultural Ministry, Anabaptist Mennonite peace and justice theology attracts and stirs passion in newcomers to Canada. “Some of these people were refugees and had experienced persecution in their home countries. That’s why they fully appreciate and agree with the Anabaptist values,” Lo wrote in an update on multicultural ministry.

Multicultural celebrations

This year, several of MC Canada’s multicultural congregations celebrate anniversaries and special events:

• 30th anniversary of Toronto Chinese Mennonite Church, Ont.

• 15th anniversary of First United Spanish Mennonite, Vancouver, B.C.

• Calgary Chinese Mennonite Church, Alta., celebrated the installation of lead pastor Joseph Liou.

• Western Hmong Mennonite Church, Maple Ridge, B.C., joined both MC British Columbia and MC Canada.

• Calgary Vietnamese Mennonite Church, Alta., held a Vietnamese Sunday service in Saskatoon, Sask.

• Korean Anabaptist Fellowship in Canada celebrated its annual gathering in Calgary during the MC Canada assembly there.

For discussion

1. How homogeneous is your congregation? How long does it take for “outsiders” to feel welcome? What extra challenges does someone from a visible minority have to feel accepted? What should Mennonite congregations do so that people from other cultures can feel welcomed and included?

2. Do you think all Mennonite congregations should be intentionally multicultural? Why is it important? Can a denomination be called multicultural if it has congregations of different ethnicities, or does it require that most congregations have a good variety in the racial mix?

3. What are the barriers or challenges for congregations to become multicultural? Joon-hyoung Park refers to the style of worship and communion as “trivial practices” that we need to be willing to change in order to be more accommodating to those of other cultures. Do you agree? What role does language play in isolating cultures from each other?

4. How much do congregations that worship in a language other than English feel part of Mennonite Church Canada or their area church? Do you think English-speakers feel or act superior to Mennonites whose first language is something other than English? What needs to happen for Mennonite churches to become more multicultural?