Canadian Mennonite

Volume 13, No. 2

Jan. 19, 2009

Ministry to all members of the body of Christ

From bipolar disorder to schizophrenia and Down syndrome, read stories of challenge, hope and healing when the church embraces opportunities to minister to—and with—those with mental illnesses and developmental challenges with the same care as they do to those who can sit quietly in the pew each Sunday, intellectually absorbing the sermon’s message and applying it rationally to their lives.

Responding to the bipolar parishioner

Ben’s parents were shocked that their son would think and say such things. They were worried about his mental health and well-being, and they were mortified since they knew many families sitting in their small town emergency room.

People, like Ben, who have bipolar disorder—and their families and friends—find themselves in circumstances they never would have imagined. Since mental illness occurs at the same rate in church members as in the general population, it is important that congregations learn how to interact with people affected by conditions like bipolar disorder.

What is bipolar disorder?

Bipolar disorder has two components: depressive episodes and manic episodes:

• A depressive episode may include a loss of interest or pleasure in what used to be enjoyable, irritable moods, dramatic changes in weight or appetite, insomnia, fatigue, feeling worthless or guilty about everything, difficulty thinking or concentrating, and recurring thoughts of death or suicide.

• A manic episode may include times of feeling larger than life, needing little sleep, being more talkative than usual, racing thoughts, being easily distracted, bursting with goal-directed activity, or being physically agitated or acting impulsively (including doing things that may have painful consequences, like spending sprees, sexual indiscretions, gambling or driving recklessly).

Problems for the church

A belief that mental illness is the result of sin or Satan’s influence is relatively common in some churches. These beliefs make it hard to walk compassionately alongside a person with mental health challenges and they may increase people’s fear of relating to someone with bipolar disorder.

Another church issue may be the time and care required to be with a person during the most painful parts of their illness. Caring may be difficult when the person doesn’t change, or when the illness causes them to be unpleasant or challenging to be with. Congregations may tire of going through the cycles of crisis, intervention and care.

By acknowledging those issues and fears, they can be addressed by gathering information and knowledge. Organizations like the Mood Disorders Society of Canada (mooddisorderscanada.ca) offer information and reading materials, and contacts to specific agencies. A counselling agency or mental health professional might offer an adult education option Sunday mornings, or provide information or suggestions to pastors, deacons or other congregational caregivers.

A great problem in the church is that people with mental health issues often disappear—sometimes by choice and sometimes because they are ignored or misunderstood. People with any medical problem, including mental illnesses, tend to do better when they have social and family supports. When a congregation asks, “How can we help?” this is a great resource.

Theological education

Sometimes churches look for theological hints or biblical clues when it comes to understanding mental illness. In biblical times there were few ways to explain or understand mental illness: “Go and sin no more.” “Be healed.” “Hard heart.” “Choose the good things.” “Don’t be anxious.”

Misusing these phrases and attitudes can imply that people with bipolar disorder are choosing sinful behaviours and attitudes, and that they should be able to triumph over their illness through confession, their spiritual relationship with God, and willpower.

Forgotten at times are the stories of Elijah and Jonah, who both begged God to let them die, and also the Psalms in all their raw humanity: “My tears have fed me day and night,” cries the psalmist to God when he is down and out. Forgotten also are Paul’s “thorn” (a burden he had to bear that would not go away) and his admission in Romans 7:14-15 about not being in control of his behaviour and not understanding his own behaviour. These are examples of understanding and mercy that we can identify with when we or a family member suffers with mental illness.

The Bible is clear that God’s people are to be a light to the world. We are to be leaders in compassion and justice. When the church seeks to be a compassionate light to the world, it begins by acknowledging and identifying with a person’s suffering. It works to include people with mental illnesses in the congregation.

Valuing gifts, judging not

If we take seriously the image of the church as a body, we must ask what each person has to offer to the community. “In fact, some parts of the body that seem weakest and least important are actually the most necessary. . . . So God has put the body together such that extra honour and care are given to those parts that have less dignity” (I Corinthians 12:22,24).

Often we think of those with bipolar disorder as a burden to the church. However, each and every person has gifts. One of the best ways for a person to feel a sense of belonging is to be a participant, to have something to offer that others need. The body is made up of many parts, and when we are open to diversity we are enriched, even if we may be uncomfortable.

While we don’t entirely know what is going on in the person’s brain, bipolar disorder can cause thought disturbances that result in impulsive, destructive behaviour. Occasionally a person with bipolar disorder may do things we don’t understand: spending huge amounts of money unwisely, abusing substances, talking wildly about connections to the universe, acting out sexually, or acting illegally (committing theft or recklessly driving).

In the church we often have a no-nonsense approach to undesirable or sinful behaviour: We tell the person to stop sinning. The complexity of bipolar disorder, however, challenges such a basic approach to behaviour change and raises tough questions:

• When, if ever, are people not responsible for their behaviour?

• What role do physical factors play with emotions and relationships?

• How much does my brain affect my relationships?

• What about choice and tolerance?

• If a person chooses a behaviour that we have trouble with, can we tolerate it in order to remain in relationship?

There are natural and sometimes legal consequences for behaviours that fall outside the norm. How might we take to heart Jesus’ words, “Judge not lest you be judged”? Might we advocate for a person in the health care system, the judicial system, with an employer, at a store or with family members?

Mental health and worship

A very damaging aspect of a bipolar diagnosis is the stigma that comes with it. Society and the church sometimes perpetuate the stigma out of fear or misunderstanding. How liberating might it be to hear Scripture, prayers, songs and sermons that take mental illness as seriously as physical illness? What if mental health issues are spoken of using “us” language rather than “them” language?

When we have the courage to speak about bipolar disorder and mental health compassionately, intelligently and publicly, we begin to make our congregations safe places for people whose lives are not all in order—all of us, to some extent. When things are spoken aloud, they become less secretive, less shameful, less binding; they have less ability to produce fear and fearful reactions.

Preventing burnout or fatigue

While everyone has abilities to offer the church, there are some people whose problems also require much care and support. In small churches, or small towns, it may seem as though the same person, or a few people, are constantly available for crisis care or support. After a time, these people may become exhausted from their efforts to help.

There are ways to prevent fatigue. They take effort to establish, but eventually make the quality of care-giving and one’s personal life go up:

• First, have a group of people as supports for a high-needs individual.

• Second, have personal boundaries. If Saturday is your family day, set a limit on care-giving activities that day.

The church is made up of human beings in all our diversity, uniqueness, abilities and difficulties. It’s a place where we can come together to explore our common humanity and grow together into people who express our greatest potential. This is a journey we take together as we encounter a world that is often challenging. Let us delight in our relationships with one another!

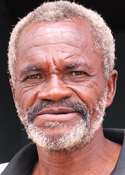

The resurrection of Joslyn

In 1990, Joslyn, a resident of Malvern, Jamaica, was wrongfully imprisoned in the maximum security prison in Kingston. He had become unstable and unpredictable due to what was later diagnosed as schizophrenia. No one—including his five children and his friends—heard from him again until 2002, when he was released. The authors visited him on his farm between October and December 2006, and arranged for the restoration of his house. In 2008, they returned and helped with the completion of the house, which took place on April 30, 2008. —Ed.

|

Welcome back, Joslyn! Welcome back to the path towards wholeness and love. Welcome home!

April 30, 2008, was a momentous day. It was the culminating event in Joslyn’s journey, with a home of his own on his own property, an ironically picturesque setting surrounded by the hills on the fringe of Malvern. On that day, his house received a final dressing of two coats of a striking “flamingo” on the outside, and “bluebell” blue on the inside. The doors received a coat of “golden brown” and the trim was painted white.

As we bid farewell and walked away along the pathway to our car, we paused, looked back and pondered. It was not only a completion of a meaningful venture; it was a significant symbol of Joslyn’s personal development and recovery from the scourge of schizophrenia, and his being imprisoned for it.

Following the completion of the job, Joslyn was “beside himself” with excitement and satisfaction. In a completely normal and orderly state of mind, he eagerly assisted the painters and watched the transformation of his house from a dull grey cement finish to an attractive glow, inside and out.

When the job was completed, he, like an “eager beaver,” and completely self-motivated, went about meticulously putting his modest possessions, including his clothes, back in exact and tidy order, all the while quietly talking, as if to himself. Every item, including the beds, had their exact location and place. No one needed to prompt him. This was a sign of a man with a healthy sense of dignity and self-respect.

A path used by neighbours walking to and from Malvern leads across his property and passes by his house. As people walked by, he would call out to greet them, even by name, even while he was busily putting his house in order.

During the course of the day we learned—and observed—that he is an industrious farmer, having planted potatoes, yams and tomatoes, cho chos (edible gourds), beans, carrots, scallions and more on his 1.6-hectare farm.

We learned more about his life in prison and about his excitement when there was hope of his release. He seemed to remember well. He talked with animation about the fear (mainly due to the unpleasant side effects) he has for the injections he needs to maintain his stability and to control the effects of his illness.

It was an occasion for his invaluable neighbours, the Lewises, to remind him that if he resists—and the injection is delayed—he needs a double dose and the side effects are then even more severe. Although there is a residual fear that he will slip into a state of mental instability, the Lewises have promised to never forsake him as long as God grants them health.

Joslyn is now surrounded not only by the hills of Malvern, but also by caring neighbours and relatives. His five children, from whom he was separated when most of them were very young, are also returning for visits and are demonstrating their revived love for their father.

Wholeness. Joslyn is no longer “dead,” as his family and community were made to believe so many years ago. By the grace of God, he is alive and well with medication.

And so it was, as we walked away from the site of the home glistening in the bright Jamaican sun, we glanced back along the trail in the woods leading to the main road. We stopped, and with emotion, thanked God for evidence of his grace and love in the person of another life restored.

Sermons from Down syndrome ministers

|

Dave Gullman is pastor of Pleasant View, Inc., a wonderful organization in Broadway, Va., supporting people with disabilities. He recently shared a lesson by one of the people he pastors, who happens to have Down syndrome. Among people who work and live with those with a range of abilities and disabilities, this is not that unusual, but I share it (with his permission) because we can all learn something profound.

Many of the people connected with Pleasant View attend their own congregations each week, but one Friday evening a month they gather for their own “Faith and Light” service, where they help lead worship services with Dave as pastor.

The participants enjoy performing dramatic re-enactments of Bible stories, like anyone else. On one Friday evening, John, a man with Down syndrome, played the part of the Prodigal Son (from Luke 15) who asks for an early inheritance from his father and then proceeds to “live it up” with prostitutes, alcohol and the like.

Dave, as pastor, narrated the story. He said that shortly after the re-enactment began, “the story began to take on a life of its own.” John, as the Prodigal Son, proceeds to dole out his inheritance to many of the worshippers gathered that evening and shares his root beer with them. The narrator gently puts an end to that to get on with the story.

As the story goes, the Prodigal Son realizes his mistakes and asks his father for forgiveness. His father welcomes him home and throws him a lavish party. If you know the story, the older son, who has faithfully worked for his father while the younger son is blowing his inheritance, becomes angry and stays outside of the party room.

Dave, as pastor, intended for the drama to stop then and speak briefly about the lessons learned from the story.

But John is not done. He sees his older brother on the outside of the circle and goes to him and acts out words of love and reconciliation. He urges the older brother back into the circle of the welcome home party.

Dave worried that things were getting a little chaotic that night “until I saw that John had understood the deeper reason for Jesus to tell this story: the younger son, in John’s interpretation, takes what he has learned from the father and extends that same love to the older brother.”

He concluded, “Once again, someone with a disability, when given the chance, has ‘preached’ the message of the night.”

I had to think of a sermon preached at my own congregation by Gary, who is totally non-verbal, at least as far as I know. When Gary first started coming to our church, he was frequently fearful and agitated; the caregivers who accompanied him would sometimes take him out of the service if he became too agitated. Over the years, as he was challenged by the people at Pleasant View to grow in his social skills, he became relaxed, obviously enjoying the interaction with other worshippers. He would willingly put out his hand for a handshake and his friendly smile frequently cheered me up.

One Sunday another woman from Pleasant View who came infrequently was upset for some reason. She began to make noise and became agitated. Gary put his arm around her in the most comforting pose and patted her shoulder, somehow wordlessly assuring her that she was okay. I will never forget the care and empathy that showed in his eyes.

John Swinton, in an article entitled “The body of Christ has Down syndrome” in the Journal of Pastoral Theology, 2004, wrote about the L’Arche communities that today include an international network of inclusive communities. (People with developmental disabilities live and work with people who do not have such disabilities.) L’Arche was founded by Canadian Jean Vanier on the Beatitudes, in particular the idea that Jesus taught that the person who is poor in what society generally values is, in fact, blessed and has deep gifts to offer.

Lest you think I idealize this situation, having persons with special needs in the life of a congregation can be messy, frankly, and Swinton also notes this in his article. Helping other adults attend to bathroom needs or clean up food from faces is not necessarily pleasant, yet very human. But don’t we all need help at both ends of life? Some simply have those needs throughout their lives.

For discussion

1. What experiences have you had with mental illness or individuals who are developmentally challenged? How well does your congregation include families or individuals with special needs?

2. Have you, or someone close to you, suffered an episode of depression, emotional distress or mental illness? How did people react? What was helpful or unhelpful? What are our biggest fears in dealing with people with special needs?

3. Has your congregation offered opportunities to learn about mental health issues? How important is it for pastors and deacons to have training in this area?

4. Are there situations in which a mentally ill person is not responsible for his/her actions? Is there a point at which a church should limit its involvement? How tolerant should the congregation be towards people with special needs?

5. How has our society’s attitude toward mental illness and developmental challenges changed? How could your congregation be more inclusive?