Canadian Mennonite

Volume 12, No. 19

Sept. 29, 2008

The drama in Mennonite history

.jpg) |

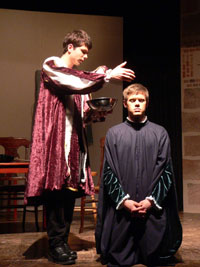

In 2007, Will and Ana (Fretz) Loewen created and performed The Shadows of Grossmünster, a historical drama about the early history of Anabaptism. The play was presented to packed houses at the Church Theatre in St. Jacobs, Ont. “Part of what made this project so much fun to work on was that it was a creative way to tell the history of our spiritual ancestors,” said Will, who wrote the script and lyrics (with music by his wife), to members of his former congregation at Tavistock (Ont.) Mennonite Church in a sermon that followed the show’s run. The Loewens, who are currently serving as Mennonite Church Canada Witness workers in South Korea, urge young adults to consider who their spiritual forebears are—young adults like themselves who were not afraid of standing up for their faith in God.

From the time that Christianity was a legal religion in the Roman Empire until the 1500s, there was one centrally controlled, universal church in Europe. Over time, the church grew quite powerful and influential. Some people began to complain that the church leaders had allowed power and influence to corrupt them. Although the church was powerful enough to punish anyone who complained too loudly, by the 1500s enough people were complaining that a lot of changes started to happen.

In Zurich, Switzerland, the local priest and a number of his students decided that they wanted to make some changes, too. They looked at all of the activities of the church and wanted to test them against the Scriptures. They disagreed about a number of things and had many public debates.

One night, as these former students of the priest gathered to study, they realized that they needed to be baptized again. They had been baptized as infants, but that ritual action no longer meant anything to them. However, these second baptisms were illegal in Europe, and this group was arrested.

|

Instead of being afraid, they refused to apologize for taking a second baptism and they even went around preaching to people, encouraging them to do the same. This kind of activity sprung up all across German-speaking Europe, and thousands of people were arrested and even executed for their rebellion.

Those rebels are our spiritual ancestors, and that was the story that I wanted to share with our audiences.

Behind the events that made them (in)famous

Having studied the history, I knew what the events were, but I needed to go farther, to see what kind of people they were. Conrad Grebel, Felix Manz and George Blaurock were very important figures in our Anabaptist history, but what were they like as people? What sort of spiritual lives did they have? What could they teach me about my faith?

One thing I really wanted to highlight was that these people were young. Conrad Grebel and Felix Manz both died before they were 28, and George Blaurock was in his early 30s during his time in Zurich. Even Martin Luther was in his early 30s when he started to rebel.

Many young adults today feel like they cannot make meaningful contributions to the church, but that is not true—and it never has been.

How many of you older folks have ever told your children or grandchildren that you were young once, too. My parents told me that a few times as well, but I’m not sure if I ever believed it. It only came a few years after I moved out of my parents’ home that I learned I can benefit from the experiences of my parents and grandparents. In the same way, when we realize that these reformers were young as well, we—as young adults—can identify with them a little better. When I think that, at 26, Felix Manz was in prison for being baptized, my problems seem a little easier to deal with.

The Reformation brought about fundamental changes to the way the church operated, and the movement was mostly fuelled by young adults who refused to keep their convictions to themselves. Grebel, Manz and Blaurock had grown up in the church. In their university studies, they had learned about the Bible, including how to read it in its original languages. When they returned to their communities, they realized they could use what they had learned to help the church, and they were excited about it.

Because of their youth, people refused to take them seriously. Because they hadn’t been properly given any church authority, a lot of people figured they didn’t know what they were talking about. But they knew. If those young people could be so confident, so could I. If they could make their faith vitally important to them, so can young adults in our time. If we are going to hold up those young adults as our heroes, then we need to give today’s young adults more credibility.

Differing times, same faith

In many ways, their time was different from ours. We have a higher standard of living, we know more about what is going on in our world, and we no longer live in a world that is dominated by a corrupt church. Some would argue that we think differently because we’ve experienced different things. However, we can easily find a number of similarities that may help us to see a little better how their minds and their world worked.

In those days, the gap between the rich and poor was growing. They lived at a time when increasing communication technology (the invention of the printing press) added to the moral confusion of society. They struggled in the shadow of institutions, governments and the church, which were hesitant to make necessary changes. Aren’t those things we struggle with as well?

A lot of people today see hurricanes, floods, droughts, starvation and disease, along with the wars and rumours of wars that fill our newspapers, as signs that the end is near. Jack van Impe has been on TV for more than 40 years saying that the end of the world is upon us.

Life in 16th century Europe, however, gave people even more reason to believe that the end was upon them. A number of plagues had swept across Europe, killings millions of people. A new and emerging form of economics caused poverty and starvation for a large number of working-class people. An Islamic army was attacking from the East, and nobody knew how strong they were or how much damage they would do.

Referring to the Scriptures, Christian leaders at that time looked at the events of their day and could very easily identify the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. Almost all Christians at that time, including our spiritual ancestors, believed that the end of all things was imminent.

This belief in impending danger did not cause them to relax and wait happily to be “raptured” into heaven. In fact, it meant the very opposite. The clock was ticking for them, and they wanted to make sure that they were right with God. They thought the world would end in the blink of an eye, in their lifetimes. There was no time to relax. They needed to ready themselves and the world around them to prepare for the return of Christ.

They were in a constant state of readiness. Are we? No matter how you interpret the end-times prophecies of the Bible, God has called us to be ready. Do you think you have time to fix your relationship with God, with others and with creation somewhere down the road? We don’t have time! We need to make things right, now.

Rejecting old ideas

For centuries, church leaders had said that the common people were not capable of reading the Bible on their own. The Reformers rejected this idea, and they made sure that the Scriptures were available to all people. They did this because, in their reading of the Scriptures, they found a liberating and life-giving message.

All their lives they were taught that forgiveness came through the priests and that connection with God could only be achieved through church rituals. Looking at the teachings of Jesus, and the actions of his followers, they knew that things were supposed to be different.

It’s important to recognize that these weren’t angry people who looked up Bible verses to back up their opinions. These Reformers were frustrated with what was happening in their churches, so they looked to the Bible to see if a model existed that they could follow.

Baptism was a ritual of the church, but the government was a part of it, too. Not only did the parents have to pay the priest to perform it, baptisms were how state authorities recorded the births of children for citizenship and taxation purposes.

People like Felix Manz felt that this had become an empty ritual, and so they turned to the Scriptures, looking for any kind of support for it. When they looked to the Bible, they found stories like the one about Philip. While Philip was walking down the road, he was called by God to run alongside a carriage that was passing by. The man inside was an Ethiopian eunuch. Some would have considered this man unclean, but Philip talked freely with him. The eunuch was reading from the Jewish Scriptures and asked if Philip could help explain what he was reading. Through his studying and this conversation, the eunuch comes to understand the good news about Jesus and, when he does, he asks Philip if he can be baptized.

This was the model of baptism that our forebears found in the Bible. People would come to faith and they would ask for, and be given, baptism. The Anabaptists took from this a sense of timing and order that they thought was important, but they also saw people who took ownership of their baptism and were committed to living it out.

Their initial baptisms having lost all meaning for them, they needed to find a way to take their baptism seriously. For them, rebaptism was the solution. Through baptism, we leave behind our sinful ways and enter into a committed relationship with Jesus; we stop working for, and thinking only of, ourselves; we promise to work within the body of Christ, which is the church; and we strive to build up the kingdom of God.

Biblical fidelity

The Bible gave these Reformers a model by which they wanted to build up the church, but they also viewed it as a double-edged sword. They used what the Bible said to attack the injustices of their society, but also to cut out the parts of their own lives that needed correcting. For them, the Christian life required total submission to God’s law and something that they called gelassenheit, total yieldedness to God’s will. And they believed that God’s law and God’s will for humanity were revealed to them in the Bible. The Bible also provided comfort to them, in both good times and bad.

I wrote a scene in the musical where Blaurock, Manz and Grebel escape from prison. In that scene they sing about celebrating their freedom. The final verse of that song is taken from the passage from the book of Psalms. There is some intended irony listening to three men who were prisoners sing these words, especially since they were thrown in prison in the first place for breaking the laws of the church:

We praise our Lord God with the Psalmist/

For a love that’s unfailing which God promised.

Lord, don’t take your truth from what we say/

We will answer the ones who mock our way/

We’ll obey your law for the rest of our days.

To your commandments we lift our hands/

We will meditate on your statutes, all your commands.

We seek your precepts and follow them/

We’ll speak before kings quite unashamed/

We walk in freedom until your kingdom comes.

For discussion

1. Will Loewen points out that early Anabaptists were young adults. Do young adults feel they make a meaningful contribution to the church? Are young adults today apt to be radicals, looking for change? What things might radicals want to change today to make the church and faith more meaningful?

2. Loewen wrote a musical play to remind us of Anabaptist history. Is this an effective way to engage us in what our spiritual ancestors faced? What other art forms have you seen used, or can you imagine, that can engage us in thinking about our faith?

3. In the 16th century, people lived in fear that the end was near, says Loewen. Why might we be more complacent and less concerned about end times? How does our society respond to natural disasters or global warming? Should we be putting more emphasis on the need to be ready?

4. Early Anabaptists didn’t use the Bible to back up their opinions, but looked in the Bible for a new model for baptism and to find God’s will. How do we use the Bible? Does baptism today carry the same meaning as it did for the Anabaptists? Do Mennonites still try to live in total submission to God’s will? Can you think of some examples?