Canadian Mennonite

Volume 12, No. 7

March 31, 2008

Video Games

No big deal? Why Mennonites play Halo

|

How do you, as a pacifist Mennonite, justify playing a violent game like Halo?” That was the question I got through the telephone one lazy afternoon. I stopped for a moment, nervously chuckling. “Heh. Um, well, you see. . . .”

I trailed off, my voice trying to hide the sheer panic spinning in my mind. “Halo? Mennonites? How do you justify that, anyway?” I asked myself.

Not hearing any answers, I immediately started going through the standard catch phrases.

“What else am I going to do?” Too wishy-washy.

“It’s not that bad.” Ugh, that’ll require an explanation.

“I really need to go. I smell something . . . burning.” Hey, there’s a winner!

Halo 101

After the editor of With (where this article originally appeared in the Winter 2007/08 issue) hung up, I knew she expected I would write a small explanation or apology—I can’t remember which—on how some pacifist Mennonites justify playing Halo.

Prepare to be disappointed.

First off, let me give you a little background on this Halo. It was released way back in 2001 for the Xbox video game console. Since then, it has been released for PCs as well. It is rated “M” for mature, a rating very similar to “R” for a movie, because of “blood and gore” and “violence.”

The game revolves around a super-soldier named Master Chief whose goal is to stop an alien force, the Covenant, from destroying all humans. Compelling, huh?

During most of the game, you’ll find yourself looking from the perspective of Master Chief. So if Master Chief is holding a weapon, you would see his back, as well as his hands holding it, and an aiming scope in the centre of the screen.

You are expected to beat the game by, at the most basic level, depositing small fragments of lead—propelled at a high rate of speed—into the bodies of your enemies, until the entrance and residence of these said fragments impede the normal operation of any of their primary biological processes.

In short, you’re supposed to shoot the aliens until they die.

This immediately poses a bit of a problem, as you are put on the forefront of a war, spearheading an effort to rain destruction upon an alien race that would love to do the same to you.

No room for Anabaptists

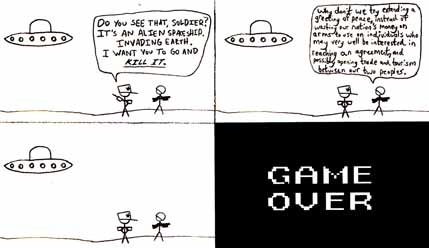

Mennonites have taken a stance of peace when two groups create war with one another but, unfortunately, that is just not possible in the game of Halo. Nowhere in the game does it allow you participate in peace negotiations—or to write up a truce of any kind.

Kill the aliens

In the single-player mode, killing your enemies is the only way to reach the end. And kill you do. While you are never pitted against other humans, you’ll find yourself up against a variety of aliens, from half your size to over three times as big, and even zombie-like creatures, each with their own colourful blood. Red. Green. Purple. Blue. Orange. Much like the colour of Smarties . . . but in tougher, mobile packaging . . . shooting at you with lasers . . . and piloting spaceships.

Regardless of the fact the gore never gets beyond what is shown on various shows on TV, or that you’re fighting fictional aliens, the content of the single-player game is very difficult to justify for a Mennonite. And it should be. Many people like to breeze over it with such phrases as, “It’s just a game,” and, “It’s not real.” But I can’t.

Granted, I love playing Halo, and looking from the outside in I can see how easy it would be to call us Halo-playing Mennonite youths “hypocrites.” But in this case, the word is totally justified. How can we say we dislike war when we are participating in digital battles ourselves? While it’s not outright hypocrisy—that would be declaring you’re a pacifist, but still jumping at the chance to go to war—it is a form of it. It’s the same thing as looking down on adultery, then running home to finish writing your saucy romance novel. It’s not physically the same, but mentally there’s no difference.

A kinder, gentler Halo

In the multiplayer-game mode, you and up to 15 of your closest friends can shoot it out in a variety of matches, the two main ones being Deathmatch (where you see who can score the most kills in a set amount of time) and Capture the Flag. The main problem here is that, instead of aiming your gun at computer-controlled opponents, you’re gunning for an enemy that is controlled by your buddy sitting next to you.

But I don’t look at it that way. I view it as a competition between friends, much like a quick game of basketball or football. Like those sports, it’s a place where you can show off what little skills you love to brag about. And like those games, if you’re not a team player you’ll end up losing.

Granted, Deathmatch doesn’t require much strategy at all, but Capture the Flag absolutely demands it, as well as communication and strategy between you and your teammates. It’s a really good feeling when you can organize a plan, change it on the fly, adapt to the other team, and watch the scheme come together seamlessly.

No big deal?

“But that still doesn’t excuse the fact that you’re shooting each other,” you might say aloud, hoping that somehow this writer will try to come up with some witty retort.

Well, there’s no witty retort here. I fully agree with you. It really doesn’t excuse the fact that we’re shooting each other.

But, hey, I had to try.

The thing is, to a lot of youths this moral dilemma isn’t really a big deal at all. When I posed the question that I was asked to some of my friends, they all did the same thing I did. They chuckled. Then they said something was burning.

Many of them simply admitted they hadn’t really thought of it, or that it’s not that big of a deal. And I believe them. To us, this stuff really isn’t that big of a deal.

Should it be?

To me, at least, if I really want to belong to the Mennonite Church, and if I really want to live by its beliefs, I need to at least think it over, talk it out with a variety of people, and, most importantly, pray about it.

Will it end with me giving up Halo and its ilk? I don’t know yet. Will I be weighing the morals that a game is impressing on me from now on?

Oh yes.

Honouring Jesus: The play’s the thing

|

Meaningless, meaningless . . . everything is meaningless. That’s what the wisest man who ever lived said. But some stuff is more meaningless than others. We argue which. Our brains bend and strain, trying to defend our guilty pleasures and bring meaning into what we secretly dread might be meaningless. We must do this because we love these things.

And isn’t the pleasure we take from them reason enough to engage in them? Of course not. We all know that. But the society around us does not. In our society entertainment has intrinsic value. Something has worth if someone enjoys it.

Of course, sometimes one person enjoys it and another does not. People of every generation have adored something their parents considered utterly pointless and devoid of value (meaningless, one might say). At one time it was the radio, then TV and movies, and now—are you ready for it—video games.

Parents argue that their children are filling their young minds with violence. Young people don’t answer because they’re busy enjoying themselves, and society has trained them to believe that their parents and elders can’t possibly relate to their world and don’t know anything about anything.

Those who play games argue correctly that there are many different types of games and that it’s not fair to paint them all with one broad stroke. That makes sense, but young people, if they are honest, will often concede that the vast majority of games—and certainly the most popular ones—are violent or sexually exploitive, or both.

I don’t mean to present this so one-sidedly. My heart goes out to those people, young and old, who love to game (yes, “game” is now a verb) and actually consider their actions. They head to the Bible for answers and note, with sincere disappointment, that the Bible doesn’t say a thing about video games. That means it’s up to each person, right?

The early Christians didn’t have the Bible in front of them like we do today. When Paul first came to Corinth, those who became Christians didn’t have any written guidance beyond the Old Testament—which Paul, their spiritual father, interpreted in a pretty bold way—and the verbal stories and rules he passed on to them. They had a terrible time figuring out what socially popular things they could keep doing and what things they had to give up. They tried to think everything through logically, but they just ended up talking themselves into doing what they liked to do. Paul hammered them over these choices and, believe it or not, his words speak directly to our questions about video games.

There was a group of particularly spiritual Corinthians who noted that, since there is only one God, all idols are really just hunks of wood and stone, and, therefore, it was no big deal to go to their temples and take part in pagan eating rituals. Really. In fact, these guys looked down on the others because they weren’t strong enough in their faith to go and hang out at Apollo’s temple.

Paul argued in I Corinthians 8 that these people were not nearly as smart as they thought they were, because they were actually enticing others to go to a place where they were sure to sin (much like encouraging a sober alcoholic to frequent bars because drinking isn’t a problem for you). So for the sake of a party, these Corinthians were willing to destroy their spiritual brothers and sisters.

Those who claim that they are personally unaffected by the violence they are practising on the TV or computer screen should be aware of how their actions are influencing others. So does this mean that it’s okay to play these games if we ourselves are unaffected and we keep things to ourselves?

The argument that something is not personally “harmful” is a poor one for any follower of Christ. We cannot label the words or actions of our radical Messiah as neutral, at least not by any definition I’m familiar with. His words, actions, thoughts—his very being—declared and ushered in the kingdom of his Father. I don’t know how much Jesus played. I don’t know which sports he enjoyed, if any. I don’t know what he did for fun. But it’s the things I do know that demand my life. Not some of it, or a large part of it . . . but all of it.

We don’t have to prove that video games are harmless, let alone beneficial. That’s not the issue here. God gave us free will. We can make choices. But if we want to make choices that honour him, then we must ask ourselves—like Paul asked the Corinthians—how our actions are building up the church. Everything else is meaningless.

Violent video games: What concerned Christians can do

“One of the most effective ways for Christians to be salt and light is by simply confronting the culture of violence as entertainment.”—Lt. Col. David Grossman

David Grossman is an American military psychologist. He has determined that the tools and tactics used to train soldiers to kill are the same as those employed in the media entertainment industry, specifically, in video games. “Every time a child plays an interactive video game, he is learning the exact same conditioned reflex skills as a soldier or police officer in training,” he stated in a 1998 Christianity Today article.

What is wrong with violent video games?

Games are built on violence and little else. Many computer and video games sold today are built exclusively around violence and aggression. The goal of the player is simply to shoot or blow up any person or creature that appears on the screen. There are no opportunities to develop problem-solving or communication skills.

Violence is rewarded

Most games reward a player’s skill by moving him to a new level of violence. As the player masters this level, the amount of violence increases. There are rewards for those who become skilled at killing. Moreover, as players associate game-playing with leisure activity or a favourite snack, they come to associate the violence on the screen with pleasure. Killing becomes a pleasurable activity.

Increase in violent behaviour

A growing body of literature links the playing of violent video games with increased levels of aggressive behaviour. Although not every child or youth who plays a violent game will behave in a violent way, some will, particularly when there are other risk factors at work.

Interactive nature

Initial studies indicate that the negative effect of playing video and computer games is greater than that of simply watching violent TV programs or movies because of their interactive nature. Children and youths are not only watching acts of depravity, they are participating in them.

Distorted images

Violent games, especially first-person shooter games, portray all those who appear on the screen as enemies to be destroyed. Where women exist, they are usually helpless victims; occasionally they are violent predators. In almost all cases, the women have very sexy bodies and have few clothes on.

Violent video games go against the biblical teachings that:

• All people are created in the image of God.

• We are called to love our enemies.

• Men and women are to relate to one another with justice and respect.

• We are to think on those things which are pure and honourable.

What can Christian parents do about this problem?

At home:

• Monitor video game play even more vigilantly than TV viewing.

• Limit game-playing time to no more than an hour a day.

• Become familiar with the games your child is playing.

• Purchase or rent only games that are recommended for your child’s age. Be aware that “Mature” games can be downloaded from the Internet.

• Provide alternative ways for your child to spend time.

• Do not put computer or video game sets in your children’s bedroom where they can play behind a closed door.

At church:

• Discuss your concerns with other families; pray together for guidance.

• Hold a workshop or adult education class on media violence.

• Provide healthy activities for children and youths.

In your community:

• Share your concerns with the managers of stores selling or renting games.

• Let the provincial government know you support a regulatory system for the sale and rental of video games—as exists for movies.

For discussion

1. Steve Friesen says that in our society “entertainment has intrinsic value.” Do you think that something is worthwhile if someone enjoys it? How much does entertainment (movies, TV, etc.) influence our moral values?

2. Do you accept the idea that violent video games influence the people who play them, making them associate violence with pleasure? How much does this violence translate into the real world?

3. Travis Duerksen says that to young people, “this stuff really isn’t that big of a deal.” Are young people just blind to the danger or are older people just over-reacting to a new form of entertainment?

4. Are there video games that teach positive values? Are there some ways that games can be used to build up the church?