Canadian Mennonite

Volume 11, No. 17

September 3, 2007

Hope and the Dragon

Teen pens book of hope for others facing frightening battles with cancer

Fiske, Sask.

|

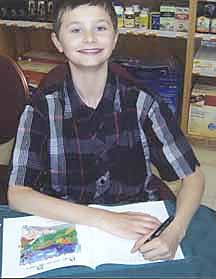

He’s only 14, but already he’s written a book, met former prime minister Paul Martin and travelled to Disney World to represent the Children’s Miracle Network Telethon.

Matthew Epp, who beat back a rare form of cancer three times, lives just outside of Fiske with his two younger siblings. Modest, with an engaging smile, the young author from this small town has done more in his life than most teens his age. He’s also endured more pain and looked death in the face more often than most, yet his quiet, simple faith carries him one day at a time. By the time he was two, Matthew was in treatment for Wilm’s Tumour, a cancer of the kidney.

At 11, while attending camp, he wrote a story about his experience. Using an encouraging idea from his mother, Matthew wrote a medieval tale using a dragon to represent the frightening cancer. Impressed, the camp director sent a copy to his mother. She, in turn, e-mailed it out to various family members.

Matthew’s grandmother decided to submit it for a contest that Aaspirations Publishing in Toronto was holding. The story won first place at the company’s first annual writing contest in 2006. This past May, Hope and the Dragon was published and Matthew went on tour.

The tour included Toronto, Regina and Saskatoon, and Matthew did book signings and media interviews for two weeks straight, including an appearance on Canada AM.

“It was tiring,” he admits.

Since there are very few books dealing with the subject of children and cancer, the story, which has been released in paperback and hardcover, has widespread appeal, as evidenced by comments found on the publisher’s website (aaspirationspublishing.com). Posted there are thoughts from Stephen Harper (“Your message of hope, faith and courage is an inspiration to those battling their own dragons”), broadcaster Pamela Wallin and other well-known individuals who have read the book and felt an emotional connection to this young man with his confident smile.

Asked if he’s thought about what he wants to do in the future, Matthew is ready with several ideas. “I want to be a chef and start my own restaurant,” he says. “I’m starting to enjoy cooking now.” Teaching high school, especially in other countries, also holds a certain appeal. And he hasn’t ruled out studying to be a doctor either.

Book Review

Vanquishing Voldemort

Why Harry Potter had to be a wizard

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows. J.K. Rowling. Raincoast Publishing, 2007.

|

Spoiler warning! For those of you who have not yet read the final installment in the Harry Potter series, this article contains spoilers so you might want to wait!

Over the last several years I’ve had hundreds of conversations with Christian parents about whether or not our children should be reading J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter books. Harry’s status as a wizard is usually the issue. But I’ve come to the conclusion that the fact that Harry is a wizard is exactly what makes the books so good and, I believe, appropriate for Christian parents to read to their children.

The fact that Harry is a wizard means that he can’t place the blame for everything bad in his world on magic. Since Harry is also capable of magic, he has to make choices about what to do with his powers. When Harry finds out that he actually has something in common with the evil Lord Voldemort, he fears he too will be capable of evil—a potential we all have to face. Professor Dumbledore says it best: “It’s not our abilities that determine our character, Harry, it’s the choices we make.”

And while Rowling didn’t set out to write an allegory in the style of C.S. Lewis, her books have obvious Christian—even Anabaptist—themes within them, particularly the final installment: Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows.

The protagonists aren’t exactly pacifists; the Order of the Phoenix is created to fight against Voldemort and his Death Eaters. Even Harry and his friends create Dumbledore’s Army, but they do so in order to learn defensive magic. Still, Harry faces the temptation to use the “unforgivable curses” as he wrestles with his hatred of his enemies.

In the journey to this final book, Harry’s goal has been to defeat Voldemort, but it isn’t until now that he realizes that Voldemort can only be defeated by Harry’s own death. Harry accepts this and faces his enemy alone, unarmed, willing to die to save his friends.

And so he dies. At least, the evil in him does; but Voldemort can’t kill the good within Harry. When Harry comes back, Voldemort’s power is vanquished. The evil Lord is finished. Sounds familiar doesn’t it?

As a parent, the books have become a way for me to talk about these life-and-death themes with my son. We read them aloud to each other as a family, which is a gift in itself, and our interaction and discussions have been wonderful opportunities to discuss our faith.

Each parent needs to determine whether their own children should read these books, but they shouldn’t be dismissed simply because they are books about wizards. Keep this in mind: Fiction is truth-telling in another form—using the fantastic to bring out the truth about our own lives and world. Rowling does that in a wonderful way. If your children are mature enough to handle the content, then the books provide a great opportunity for you to talk about things you might not talk about otherwise.

Film Review

Does The Simpsons Movie demean Christianity? Doh!

The Simpsons Movie. Directed by David Silverman. Written by Matt Groening, James L. Brooks, et al. 20th Century Fox, 2007. PG.

“This book doesn’t have any answers!” exclaims Homer Simpson in frustration as he pages through the Bible early in this summer’s hit film, The Simpsons Movie. The reason for Homer’s search for answers is Grampa, who is “speaking in tongues” while writhing in the aisle of the Springfield church.

Poking fun at Christianity has been a prominent feature of The Simpsons TV show for 18 years, so this irreverent scene does not come as a shock. But is it an example of a generally negative attitude toward Christianity—or is it merely critiquing what the writers (including creator Matt Groening, who has Mennonite roots) see as excesses of the Christian faith?

For nearly two decades now, Christians have held differing opinions on this question. Some have found The Simpsons offensive, saying it promotes questionable morals and consistently demeans Christianity, specifically by suggesting that Christians are fools who are out of touch with reality. Others maintain The Simpsons has largely portrayed the Christian faith and Christian values in a favourable light, critiquing primarily religious hypocrisy.

In the end, viewers will need to decide for themselves whether they find The Simpsons Movie offensive, but I, for one, was surprised by how gentle, inoffensive and spiritually affirming the film was.

Christianity does not actually play a major role in the film, with only a few references—including a jibe about “intelligent design”—outside of the early scene in the church. But there are numerous scenes that affirm Christianity and an ethical life.

The film concerns an environmental disaster in the town of Springfield, caused by Homer, and the overreaction of the Environmental Protection Agency, eventually leading to the planned annihilation of the town and its residents. Homer faces a lynch mob and escapes to Alaska, where he meets someone who will force him to confront his selfish ways.

He eventually learns that other people are as important as he is, which, for Homer, is a huge revelation. Along the way, Homer is confronted by his wife Marge, who asks him how he could ignore the warnings of their daughter Lisa, and stupidly cause the disaster in the first place. In my favourite line of the film, Homer responds: “I don’t think about things!”

There is a clear moral lesson here: If people don’t start thinking more about issues like global warming and poverty, a global disaster is all too likely.

Meanwhile, son Bart discovers that perhaps the evangelical Christian neighbour Ned Flanders—depicted as a genuinely kind and caring person—would make a better father than Homer. And, of course, Lisa Simpson, the social conscience of the family, is trying her best to raise awareness on environmental issues.

Groening has been quoted as saying that Lisa is his favourite character: a stubborn idealist crusading for love and justice. She is, in fact, usually depicted as a Christian activist, not unlike many Mennonites I know and admire.

The Simpsons Movie is a very funny and intelligent film. Yes, there are jibes against Christianity, but there are also positive depictions of the Christian faith. Even the writhing Grampa is later described by Marge as having had a genuine religious experience—and she is angry with Homer for belittling it.

And the film is much more interested in bashing the U.S. government, rich white men and big corporations than it is in bashing religion. While this film may not appeal to everyone I thought it was an inspired piece of filmmaking with at least one important message: We dare not be complacent like Homer.