Canadian Mennonite

Volume 11, No. 13

June 25, 2007

Forgiveness in the face of barbarity:

The story of John and Grace

Uganda

|

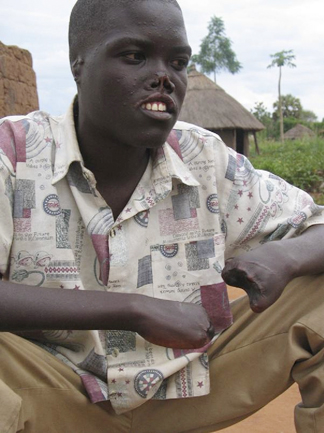

John Ochola was abducted by the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) from the village of Kabong in northern Uganda during the first week of June 2003. The rebels attacked his village in the early morning hours, surrounding his compound and leaving him no way of escape.

His captors soon began accusing him of being part of the Ugandan military. He told them emphatically that he had never attended military training or joined the Uganda People’s Defense Force (UPDF); that he had always been in his home village attending school and farming.

The rebels tormented John for a while before asking him, “What kind of sleeve do you want—a short sleeve or a long sleeve?” He learned later that they were talking about his arm; if he had chosen a short sleeve, they would have cut his arms off at the shoulder. Because he didn’t know what they were talking about, he did not respond.

They then informed him that they were going to “teach” him for his “sin” of being part of the UPDF. With that they began hacking off his nose, lip and ears with a knife. The pain was excruciating. Then the LRA rebels placed his left hand on a block and started to chop off his fingers and thumb. When they had finished with the left hand, John could see that their intention was to do the same to his right, so he implored them—all the while spitting blood—to have mercy so that he would have at least one hand.

After they had completed their butchery, his captors left him to die. But despite a loss of blood he pushed through the bush until he reached a main road. There, he met some kind people who gave him a lift to the government hospital in Kitgum, where he was treated for the next four weeks and where his wife, Grace Aromo, and his mother, Grace Akot, finally found him.

After the rebels had abducted him, they burned his homestead, including the granary that contained the harvest of groundnuts that he and Grace had recently brought home. All of their livestock—goats, ducks, turkeys and chickens—were taken and the other crops that were almost ripe were destroyed.

At the time of his abduction, John and Grace had been together for a year; Grace was seven months pregnant with their first child. As is the Acholi custom, they began their marriage by living together and had not yet begun the next process in their tradition—paying the dowry and negotiating for all of the gifts that would have to be given to the bride’s family. The groundnuts they had gathered and goats they had raised were designated for this purpose, but their efforts were now thwarted.

In traditional Acholi culture, when the dowry has not been paid the girl is often recalled by her parents in order to motivate or “provoke” the man’s family to start working harder towards paying the dowry. Normally, the family would have given months or even years for the dowry to be paid, but Grace’s family perceived that John would never be able to pay, so they thought it wise to recall their daughter. So in September 2003, Grace’s brother came to Kitgum and carried her back to her family.

Grace did not resist being taken because she knew that this was the tradition, that her family had the right to recall her and that she had to obey. However, this was not something that was easy for her because she was committed to her relationship with John and to raising their child together.

In a testimony to her feelings—and in order to encourage John in the difficult struggle that he was going through—she wrote him the following letter within weeks of being taken away:

“Don’t think my absence from you means that I’ve abandoned you. I would have loved to stay with you right up to now. Nothing should separate us now. “What has happened cannot separate our initial plan. What if the incident had happened to me? Would you have abandoned me? It could have happened to anybody. That should not be an issue of worries. “Now I’m sending you my photographs and that should keep reminding you that I’ve not abandoned you. But at the same time, other people are discouraging me from continuing with you…. “But these negative opinions of other people will not have room in my mind. Even my brother, Olal Kenneth, is encouraging me not to worry. Things can happen to people all over the world like that. He is greeting you and at the same time praying for us.“Apoyo [thank you] and grace.” Aromo Grace

When John received this letter, he was greatly encouraged and it gave him much hope. His problem, however, was that he knew a miracle would have to happen if he was ever to even begin the dowry payment.

A month after Grace was taken from him, John was visited by a team of Canadians from Canadian Foodgrains Bank led by Mennonite Central Committee. They heard his story and were moved with compassion. When he was asked him how he felt now about those who carried out these violent acts against him, John said that he could see nothing useful in thoughts of revenge—so he had forgiven them.

|

The team put money together and gave it to the church leadership in order to assist John with the payment of the dowry. Several also gave him cash on the spot, which he used to purchase some bare necessities for his family as well as to begin a small business selling cooking oil by the side of the road.

On Dec. 6, 2003, negotiations took place between the two families, including two representatives from the church. During the discussions Grace sat close to John. After certain formalities were dispensed with, the chair of Grace’s family asked her, “Do you know this young man by the name John Ochola?” She smiled nicely and said, “Yes, I do know him.”

“If what you say is true,” he asked, “is it acceptable that you stay with this young man until death separates you?” She smiled and said, “Yes, of course.”

The chair went on to ask, “Are you going to shame us amidst any problem that you may come across as you live together?” She replied, “This is not a problem to me.”

“You have now agreed,” the chair charged her. “My advice to you is this: that you stay well, that you love your husband, and that you stay with him forever. We don’t want to hear anything about you coming back to us.”

John sat there quietly and smiled throughout.

After these preliminaries the negotiations turned to economics. Fines were levied because the baby was born out of wedlock, a dowry price was set, and gifts for members of Grace’s family were identified (goats, sets of clothing for both parents, a blanket for her grandmother and several other things).

John and Grace were allowed to stay together in Kitgum for several weeks before Grace was told to return to her family for final words of encouragement and advice before she became the official wife of John Ochola.

The meeting ended with a feast put on by John’s family and relatives. There was much joy and celebration in what John called a “miracle” that he never thought would take place. The contribution by the Canadians was a “rescue” beyond his wildest imagination.

Ontario Mennonite organizing Bending Spears film

On-again/off-again peace talks in the 20-year civil war in Uganda between government forces and the rebel Lord’s Resistance Army are now on again. Despite the great many stories of pain and suffering, there are examples of people who have decided to forgive—against all odds.

Dave Klassen, a former long-time Mennonite Central Committee (MCC) staff worker in Uganda and a member of Waterloo North Mennonite Church, Ont., is organizing a one-hour documentary film to tell these stories. He is working with Rick Gamble, a documentary TV news producer formerly of Kitchener’s CTV affiliate station CKCO-TV, and Andrew Heubner, a videographer from CKCO-TV.

The film will focus on the lives of five Ugandans who have chosen forgiveness, rather than hate and anger. John Ochola had his fingers and parts of his face cut off by members of the LRA (see “Forgiveness in the face of barbarity,” above); his wife, Aromo Grace, has chosen to love and stay with him, rather than reject him. Bishop Macleord Baker Ochola, an Anglican clergyman, continues to work tirelessly for peace alongside his Roman Catholic and Muslim counterparts, even though the rebels blew up his wife with a landmine, and raped and killed his daughter. Father Carlos Rodriguez, a Roman Catholic priest and journalist, presses for peace, shoulder-to-shoulder with Bishop Ochola and other renowned religious leaders, while grappling with the guilt of not having done enough to protect the women and children kidnapped from his parish and community. Viewers will also meet Gladys Oyat, a passionate and dedicated headmistress of a Kitgum girl’s school, where a significant number of the 900 students are former “wives” or sex slaves of rebel commanders.

The film is named after an Acholi people’s tradition, where the healing of a broken relationship begins with a community ceremony involving the bending of two spears and the sharing of a bitter herb potion.

“Compelling stories of forgiveness, and a willingness to move beyond the pain, are being played out in the lives of many Acholi,” says Klassen. “We believe passionately that these stories must be told—not just to counter our western culture’s damaging and demeaning image of Africa, but to inspire all who hear to search their own souls for a personal application of this poignant and powerful principle.”

The film’s organizers hope to begin filming on location in Uganda this summer. For more information, or to contribute to the costs of the effort, please contact Klassen at dave.klassen77@gmail.com.

Stewardship stories for the generous life (Part IV):

No gifts for Emily this year

Waterloo, Ont.

“Imagine how much money could be raised,” mused 10-year-old Emily Martin, “if every Grade 5 kid in every Mennonite Conference of Eastern Canada church brought money for a project instead of a gift to every friend’s birthday party.”

She didn’t know all the numbers to do the math, but her dark eyes sparkled as she pondered how this idea might explode. Each year she has a great birthday party with a few friends from school and church. She chooses a theme, plans activities, serves snacks and birthday cake, and opens gifts—new things that need space in a room already overflowing with old things.

Her 10th birthday was different. “I didn’t need more stuff,” said Emily.

The “alternative” gift idea had grabbed hold of Emily as she helped pack relief kits for Afghanistan at her church. Why not ask her birthday guests to bring money for relief for Afghanistan, or for another project that received less publicity, instead of bringing gifts for her?

Emily and her mother, Wanda Wagler-Martin, visited Arli Klassen, Mennonite Central Committee (MCC) Ontario executive director. Klassen explained about the “Rag Pickers” of Tiljala Shed project in India, where children sift through garbage looking for things to recycle. The lucky ones have parents to work with them. They live in shacks or on the street. With no address, schools do not accept them. The “rag-picker” project helps finance informal schooling and less than $100 covers all school costs for one child for a year, including nutritious snacks, medical check-ups and uniforms.

Helping street kids in India get to school was a perfect birthday project, Emily decided; she had seen similar poverty when her family visited Cuba. So invitations to her birthday party included information on the “Rag Pickers” of Tiljala Shed project. She suggested guests bring a donation of $10 or more for that project. Gifts for her were optional, but should cost no more than $5.

Her fifth grade friends thought the idea was great. A few brought small gifts for Emily and everyone brought money. The seven girls raised $120. One friend picked up the idea and later invited friends to bring money for an MCC AIDS project for her birthday party.

Emily’s mother was not surprised her daughter chose gifts for others rather than for herself. “It’s Emily’s way,” she said. “She’s thoughtful of others and feels deeply about people’s needs.”

“I like the specialness of a party, the energy that goes into planning and having her friends in,” Wagler-Martin added, “but I’m not comfortable with [receiving] things that aren’t necessary. There is no sense of long-term gratitude.”

She reflected on the search for contentment in today’s society and the culture that compels people to think we need to buy the best and lots of everything. It is fine to purchase quality products, she believes, but contentment is not found in consuming.

Such counter-cultural thinking has already taken root in Emily, who said adamantly that she does not like malls and that popular brand names have no appeal. When she and her mother shop, they read labels and try to avoid buying products that come from sweatshops. A great find was a basketball with a “no child labour” tag.

Choosing how to spend money, along with the discipline of giving, must be taught to children, according to Wagler-Martin. She sees Sunday school as a ready-made avenue for such teaching. The home is another avenue. In the Martin household, children receive an allowance and are encouraged to split the money three ways: giving, saving and spending, with the clear message that giving is important.

Although “stewardship” language is not common at the dinner table, Emily understands the concept. Her definition includes “helping others, giving time, love and being a neighbour.”

These thoughts have Emily’s mind already buzzing with ideas for her next birthday party and she has made one decision. This year her invitations will say, “Please, no gifts for Emily.”