Canadian Mennonite

Volume 11, No. 11

May 28, 2007

Moving past surface criticisms of religion and society

|

Religion and Alienation: A Theological Reading of Sociology, Second Edition. Gregory Baum. Novalis, 2005.

Thirty years after its original release, Novalis Publishing has released a revised edition of Gregory Baum’s exploration of the dialogue between social theory and theology.

Discarding the question of whether religion is good or bad, Baum asserts that religion itself is neither helpful nor harmful, but may have either effect with respect to the alienation of individuals. This discussion takes Baum through extensive discussions on Hegel, Marx, Freud, Durkheim and Weber, among others. Baum draws attention to how each of these theorists offers a distinct view of religion, taking great pains to demonstrate that each view contains valid readings of religion in its various historical expressions.

Hegel is understood to view religion as the source of social alienation, as it draws worshippers away from the imminent natural world to the transcendent abstract world. Marx views religion as the product of social alienation, as people attempt to create a “false consciousness” in order to justify and placate their existence.

Baum defines his project as “critical theology,” which is more a “mode of reflection” than a particular type—or branch—of theology. Baum writes that “it is the task of critical theology to bring to light the hidden human consequences of doctrine” (page 170). His critical theology addresses the problems of the privatization of religion in its approach to sin and the effects of Christian eschatology.

In his reflections on the 30 years since the publication of this book, Baum continues to support the dialogue between theology and social theory. The chapter ends with a word of hope for those pursuing universal solidarity, which Baum sees coming through the rigorous critique of neo-liberal economics.

Religion and Alienation opens new opportunities for those who want to move past surface criticisms of religion or society. Baum demands respect for the complexity of social and religious phenomena, seeking the appropriate tools to critique them. Those interested in interpreting their contexts, whether in the local church or national culture, would be well served by this work.

A shortcoming of the book is Baum’s partisan position on how religion and theology can positively impact society. In the final chapter, Baum assumes that “right-wing” expressions “detach faith from commitment to justice” (page 218) and destroy social services (page 224), without offering space for socially responsible conservatives. In an interesting turn, Baum also charges that “postmodern thought tries to remain indifferent to the poor and oppressed because the idea that they can be liberated is a dangerous illusion” (page 233). While offering valid critiques for both conservatives and postmoderns, Baum remains inappropriately limited in his engagement with both camps.

Salsa dancing prepares worshippers for prayer

Puerta del Rebaño, Chile

|

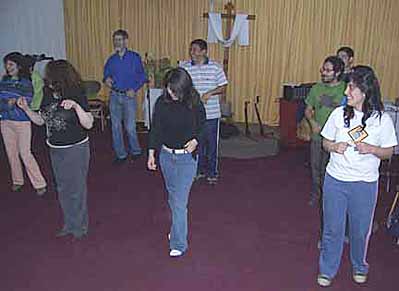

As a unique way of preparing for an hour of prayer, the lively community of Christian believers in Puerta del Rebaño engages in an hour of salsa dancing together every Wednesday night.

The church, started by Carlos González, then professor of fine arts at the University of Concepción, has always regarded the arts as very compatible with the life of the church and its activities. The unique combination of dancing and prayer grew out of the church’s resistance to forcing young people to choose between art and church activities, and “as a practical application” of a sermon that dance teacher Valentina Elgueta gave “on the body and its importance.”

Elgueta’s positive view of the body has theological underpinnings. As part of God’s creation, “the body is good and sacred,” Elgueta asserts. Christ’s resurrection was bodily; therefore, “a renewal in our faith journey is [also] renewal of our bodies,” she says.

Why salsa dancing?

“Because it is most expressive and playful…fun, upbeat and requires that we coordinate one with the other, that we touch and move in sync, and I thought it to be the best way of motivating not just the women…but also the men,” Elgueta says.

Salsa dancing before prayer increases attendance at prayer, Elgueta observes, but “more importantly…we may see it as a moment of most intense communion with God. Dancing in community is an important time of communion with God.”

Canadian Mennonite University missiology and world religions prof Titus Guenther of Winnipeg participated in this unique warm-up to Scripture study and resonates with Elgueta’s sentiments. “We felt bonded as a group after working for an hour at getting the rhythms of artistic movement right,” he says. “It was a good way to feel as we entered into prayer.”

More than a ‘nice hobby’:

Graduate artist reflects on her faith and craft

Waterloo, Ont.

|

The graduation art show depicting my art and that of my fellow students at the University of Waterloo was a huge milestone for me both as a person and as a Christian. For more than 12 years I had been learning to use the talents God had given me. In the back of my mind was the parable of Jesus about the distribution of talents and not to burying our talents. I was also motivated by a comment from the late Protestant theologian Francis Schaeffer about not leaving the arts to non-Christians.

Eden Christian College, where I attended high school, offered only music among the arts to be pursued. In my upbringing, schooling and church teaching, the emphasis was on evangelism and alleviating suffering in the world. As a result, I learned that the visual arts were not really important for Christians. They were a nice hobby, a sort of self-indulgence. Besides, I could see that the market was already flooded with “nice pictures.” So I put my desire to draw and produce images aside for a while, and got on with doing the serious and useful work that I thought the world needed.

There came a time, though, when I discovered that drawing had a useful function in my life. When depressed and harried, it relaxed me. I functioned better in the rest of my life as a result of “indulging” this hobby. Eventually, this led to my enrolment at the University of Waterloo to study art on a part-time basis—so that I need not neglect my other responsibilities.

A university art education was useful to me, in that not only did I learn the skills of my craft, but also the history of art and how it was used in society and the church in the past. It taught me to evaluate what was being said, intentionally or unintentionally. Visual art has a language that people are constantly reading whether they know it or not. I realized that as a Christian trying to abide in Jesus, I had things to offer to the church and the world.

For my graduation show, I worked on the theme of trying to express both emotions and ideas regarding pain and brokenness in individuals and groups. This observed and experienced pain I conveyed through the painting of broken glassware in a landscape setting.

One of the paintings is modelled after a medieval altarpiece. Altarpieces were installed in churches or hospitals as meditation pieces. My altarpiece, entitled “Where Two or Three…,” is an image of the church, with Christ also broken in the very centre of the painting. One could ask why the church image is in the centre of the painting or why the broken glasses representing the church are standing? Questions are important in looking at, and reflecting on, this art.

I think of my paintings as meaningful to people if they take the time to look long, intently and reflectively. They will mean different things to different people depending on their life experiences. As such, discussion among the people viewing the paintings could help them reflect on relationships and the nature of pain, and be a catalyst in dealing with the pain.

My hope is to continue to paint while acquiring an audience and venues for my art to be seen. I hope a dialogue about the concepts in the art itself, and also the nature of visual communication, will develop for the good of the world and the church.