Canadian Mennonite

Volume 11, No. 08

April 16, 2007

|

Over the course of my life I have done my bit in lectures and books to make 16th century Anabaptism visible to our people and time. I have been, and remain, an advocate for the Anabaptist form of Christian faith as put forward by Pilgram Marpeck and others.

But I have grown increasingly uneasy by the now common designation of Mennonites as Anabaptists. We seem to think that, in spite of our often-uncritical cultural accommodation, we can somehow preen ourselves with the bright feathers of a heroic tradition. And then we go on to imagine that we can be like those who were part of that tradition those centuries ago by adopting the nickname their enemies gave them.

Those of us who have studied and written about 16th century Anabaptism, including myself, have not emphasized sufficiently that our 16th century forebears were not out to separate from the old Catholic Church of their day. Like the reformers Luther, Zwingli and Thomas Cranmer, they were out to reform the one church and not to create another.

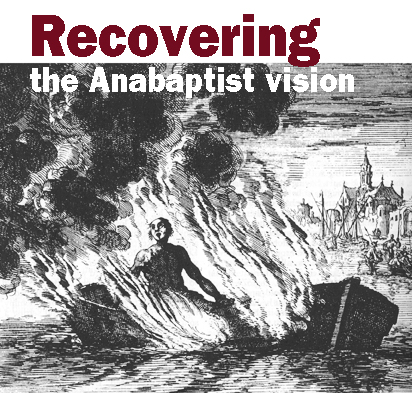

It was the lamentable consequence of an intolerant century that Anabaptist reformation efforts were rejected and came to nothing because they refused to embrace the coercive methods of the other reformers. Their vision to contribute to the reform of the one church failed, as did that of the other reformers.

What especially characterized 16th century Anabaptists was that they stood consciously against virtually everything their Christian culture took for granted. They rejected all religious coercion, and insisted that governments had no role in the internal life of the church. They rejected the emerging capitalist economic system of the time, primarily because it discriminated against the poor and defenceless. They refused to accept any justification for the use of force and killing in the defence of the gospel.

They paid an extremely high price for accepting the baptism of believing adults as a sign of commitment to follow Christ, because it was against the law and often carried the death penalty. If we in North America are going to call ourselves Anabaptists, it would seem to me that there ought to be some resemblance between us and them.

The Anabaptists of the 16th century are our spiritual ancestors and we rightly celebrate their life, witness and martyrdom by rehearsing their story. But that does not make us Anabaptists.

First, with very few exceptions, we are not rebaptized, for that is what the name means. We are not persecuted and hounded into prison for our faith, nor do we face death. We are affluent and conformed to this world in our enthusiastic embrace of consumerism and therefore don’t have the singleness of heart which was required of them for living faithfully in the face of imprisonment, torture, exile and death.

Without doubt, we are trying to live faithfully in our time and place, but it’s hard because it costs us virtually nothing to be baptized. Baptism has no life-and-death outcome for us. It is confusing because we are no longer sure about our faith; its basis keeps shifting uncertainly for us as for other Christians. Inviting to our institutions people like Tom Harpur (author of The Pagan Christ), and to have some applaud their siren voices, is a sign that we are confused about what the truth is. [Harpur engaged in a debate with Jim Reimer, director of the Toronto Mennonite Theological Centre, at a 2004 fundraiser at Conrad Grebel University College. Ed.]

Anabaptists were human and did not always get things right, but without exception they knew that their faith basis was that Jesus Christ, the Son of God, had come into the world to save sinners; that in his death they had forgiveness of sins; and that in his resurrection they had the light and power to live the Christian life. They had confidence and trust in God’s love and judgment, that would see them through the darkness of their time to the light of God’s eternal kingdom.

It is a betrayal of Anabaptism to reduce Christian faith to social activism, as we are inclined to do. We are not called to change the world by our own efforts. We do not build God’s kingdom; it is a gift God gives us when we have faith in Christ and which we may, by God’s grace, receive.

There are, however, some Mennonites who may justifiably use the name Anabaptist. They live in Vietnam, Colombia, Ethiopia and in other places in the world where they were—and are—being persecuted for their faith by repressive governments, and therefore know what it was like to be Anabaptists back then. And then there are also those who have come into the Mennonite Church from churches that still baptize infants, and who have been rebaptized. These also have a right to be called Anabaptists.

So perhaps we could dignify all of these as modern Anabaptists, and the rest of us should be content with being called Mennonites—our old nickname. If we are going to be faithful to the Anabaptist vision, then we will renounce all separatism and ethnic pride, and participate in the incomplete, ongoing reform of the whole church—to the glory of God and Jesus Christ, who prayed that we all might be one.

2007: Year of the Swiss Anabaptists

Langnau, Switzerland

A service at the Protestant church in Langnau marked the beginning of the Anabaptist commemorative year in this Swiss canton’s rural Emmental region.

More than 200 events will recall the persecution of Anabaptists, which began during the Reformation and did not end until the early 19th century.

Events include plays, exhibitions and excursions throughout Bern and neighbouring cantons in north western Switzerland.

“We, as the indirect successor to the political authorities of that time, regret the injustices done to so many and the suffering caused,” said Werner Luginbühl, president of Canton Bern’s government, during the opening ceremony on March 24. “We can’t undo what was done, but society can learn so that the mistakes are not repeated.”

The country’s existing Anabaptist community is uneasy about suddenly finding itself in the spotlight, said Paul Gerber, president of the Swiss Mennonite Conference. The challenge for Mennonites today is to remain true to their faith despite this new attention, he said.

There are 14 Mennonite congregations in Switzerland with about 2,500 members, and an estimated 600,000 descendents of Swiss Anabaptists live in North America.

Visitors from abroad are encouraged to attend an international gathering in Emmental from July 26 to 29. For more information, visit www.anabaptism.org.

—MWC release