Canadian Mennonite

Volume 11, No. 06

March 19, 2007

|

The following Good Friday meditation on the cross according to the Passion narrative of John was written and preached by John D. Rempel, assistant professor of theology and Anabaptist studies at Associated Mennonite Biblical Seminary, Elkhart, Ind.

Today is the day Christ died. We gather in awe and wonder, in sorrow and pity. We come in heartfelt gratitude. We flinch as we imagine Jesus pleading with his Father in the garden, being mocked by the soldiers, carrying his own cross.

Yet instinctively we know this is it: The salvation of the world is unfolding before our inward eye. The force of the world’s evil and the weight of the world’s sin are poised to pin Jesus down, nail him to a tree and let him die. We imagine that we are there, torn by uncertainty at what we would do—join Jesus with the Marys and John in his abandonment or desert him with the rest of the disciples?

We meet Jesus in the midst of accusation and betrayal. Pilate orders Jesus to be flogged in the hope of satisfying his accusers that this blasphemer has been rightly punished. But nothing will satisfy those who want him dead! He is a marked man. As Jesus awaits his fate, he is made the plaything of soldiers; they weave a crown of thorns which pierces his brow. “Hail, King of the Jews!” they shout in mock reverence.

It is a pathetic sight, but in the eyes of those convinced that Jesus is the No. 1 enemy of God and country, no torture can be cruel enough. The prisoner is sent out to the people, bloodied and beaten. Still the crowds shriek, “Crucify him; crucify him!”

At noon Pilate relents and hands Jesus over to the soldiers and the mob. The timing of Jesus’ condemnation is not lost on the Gospel writer. Noon hour on the Day of Passover was the time when lambs were slaughtered for the feast. Jesus goes forth as the final lamb, the last sacrifice. Once and for all he bears sin away and breaks its power to condemn.

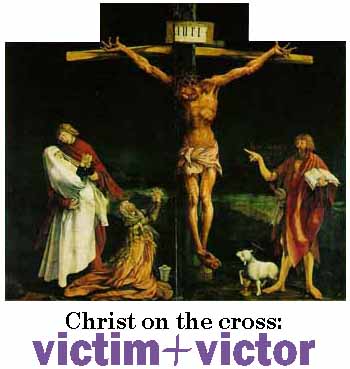

One of the most astonishing and overwhelming portrayals of the crucifixion is by the 16th century artist, Matthias Grunewald. His painting was part of an altarpiece he created for the chapel of a hospital for people suffering from syphilis. When we look closely at his depiction (see reproduction above), we see that Jesus’ whole body is covered with open lesions.

It’s hard to resist the suggestion that Jesus is being portrayed as a syphilitic. In doing so, he bears the marks of the most dreaded disease of that age. It is like the AIDS sufferer today, “one from whom others hide their face” (Isaiah 53:3). The message is unmistakable: no infirmity is beyond the compassion of Jesus, no affliction unredeemed by his sacrifice or uncleansed by his blood.

Matthew, Mark and Luke place the full weight of the passion story on Jesus’ anguish, on his willing victimhood. Indeed, who could remain unmoved by Jesus’ sweat-drops of blood in the garden, begging the Father to remove this cup of suffering? Who does not want to cry out on his behalf when judge and crowd alike scream condemnation—and Jesus is silent? Who does not groan at the sight of Jesus’ helplessness under the weight of the cross and heave a sigh of relief when Simon of Cyrene lifts the crushing burden from the condemned man’s shoulders? Finally, who is not drawn into the helplessness of Jesus’ mother and friends as they watch him being tortured from a distance?

Jesus’ dying confidence

It is not hard for us to believe in Jesus on the cross as a victim. But it is almost impossible to believe in Jesus on the cross as a victor. The special contribution of John’s Gospel to the Passion drama is the insight that, in the midst of his suffering, Jesus still seizes the initiative. About Jesus’ prayer in the garden, John wants believers to remember not only his sweat-drops of blood, but also his burning resolve.

The Gospel writer recalls not only Jesus’ silence before Pilate, but also his unflinching rebuttal of the accusations against him. On the way to Golgotha, nothing is said in the Fourth Gospel about Simon of Cyrene; what is seared into the memory is that Jesus carries his own cross. When he is hanging on the cross, Jesus does not leave his mother and friends helpless at a distance, but beckons them to within hearing distance to see to it that Mary is cared for by the Beloved Disciple. Finally, before Jesus breathes his last, he declares, “It is finished!” What he came to do is accomplished.

From the other passion accounts we remember Jesus’ dread that the God of heaven and earth might—like Abraham about to sacrifice Isaac—be forsaking his only begotten Son, delivering him on our behalf over to the power of evil. This dread was surely a part of Jesus’ dying dread.

But John insists that his readers remember something more—Jesus’ dying confidence. The cry of anguish in the Fourth Gospel is at the same time a cry of conquest. In being pursued to the cross by the powers of destruction and death, Jesus becomes their pursuer. He casts himself on the goodness of God with relentless trust; he lets himself be God’s lightning rod. All the trespasses and woes of creation crack like fire through the cosmic sky and strike Jesus dead.

Christian depictions of Jesus’ crucifixion in the West are largely inspired by the Passion story as it is told by Matthew, Mark and Luke. Jesus is overwhelmingly portrayed as the victim—the prey of sin, evil and death—as we see so hauntingly in Grunewald’s altarpiece.

By contrast, John inspires the icon painters of the Eastern Church where Jesus is depicted as a victor: he stoops to conquer. A common subject for portrayals of the crucifixion in the East shows Jesus reaching down from the cross, bending low to reach the hand of Adam in hell. Jesus stretches down into the pit to lift the first sinner, and all who came after him, to freedom. The message is clear: the power of everything that imprisons us—fear, revenge, greed, lust (everyone has their own list) is broken on the cross and we are free!

This is the reason why John wrote a unique account of the Passion, so the church would never forget that Jesus’ derision is at the same time his glorification. It is in his death that the power of love is most fully known. Yet we huddle in our prisons of fear because we refuse to believe that love can have the last word.

When we do so, we mock the claim that no corner of time and space—or of our own lives—is outside the redeeming reach of God’s love. When we hoard possessions, power and friendship, rather than risk being generous with them, we belittle the victory of the cross. When we put our confidence in wealth and military might, rather than trusting in God’s provision, we belittle the victory of the cross.

On this most solemn day of the year, words fail us, so we turn to the awesomely simple gesture Jesus shared with his disciples on the night he offered himself up.

Paul asks in his first letter to the Corinthians, “The cup of blessing which we bless, is it not a communion of the blood of Christ? The bread which we break, is it not a communion of the body of Christ?”

When we break the bread and bless the cup we participate in the very life of Jesus laid down for us. We observe Good Friday as the most sacred day of the year—because on it we re-enter that event, above all others, which rescues the world from despair. On it, Jesus became the last sacrifice, the final scapegoat, breaking the vicious circle of an eye for an eye, making forgiveness possible.

“It is finished.” The work of love is done. Now the work of love can begin.

A Christus Victor sermon

|

One of the earliest extant sermons of the church—preached at Easter by Melito of Sardis (A.D. 195)—concludes with these words:

But he rose from the dead

and mounted up to the heights of heaven.

When the Lord had clothed him with humanity,

and had suffered for the sake of the sufferer,

and had been bound for the sake of the imprisoned,

and had been judged for the sake of the condemned,

and buried for the sake of the one who was buried,

he rose up from the dead,

and cried with a loud voice:

Who is he that contends with me?

Let him stand in opposition to me.

I set the condemned man free.

I gave the dead man life;

I raised up one who had been entombed.

Who is my opponent?

I, he says, am the Christ.

I am the one who destroyed death,

and triumphed over the enemy,

and trampled Hades underfoot,

and bound the strong one,

and carried off man

to the heights of heaven.

I, he says, am the Christ.

|

“Is not this the fast I choose: to loose the bonds of injustice, to undo the thongs of the yoke, to let the oppressed go free, and to break every yoke?” (Isaiah 58:6)

In the spring of 2003 my family and I made a trip to the Philippines. It was our first visit since my husband and I had served there with Mennonite Central Committee (MCC) in the mid-1980s. We were amazed at the changes in the town of Malaybalay, where we had lived. Instead of muddy and rutted roads, there were now paved streets. Instead of daily “brown-outs,” there was now steady electricity all day long. Instead of a telegraph office, there was now an Internet cafe. It was evident that integration into the global economy had brought significant gains to the Philippines.

Then we visited Charing, a friend who had lived with us in Malaybalay. Charing, her husband Nario, and six children now lived in a remote hilly region far from paved roads, electricity and Internet cafes. Here, they tried to eke out a living on the steep hills by growing corn and bananas. They had a small one-room wooden shack which housed their few possessions: sleeping mats and pillows, some cooking pots and utensils, a few school supplies, and one or two changes of clothing for each family member. A horse and water buffalo were their prized possessions, enabling them to work their small bit of land and get their produce to market.

As we visited with Charing and Nario, we learned that small farmers like them were missing out on the benefits of the global economy. The value of their produce was less than what it had been two decades earlier. Like other poor countries joining the World Trade Organization, the Philippines was required to lower its tariffs against foreign agricultural imports. The result was that cheap corn imports flooded the market, lowering the price for locally grown corn.

Not only did Nario and Charing receive less for their produce but, because of the Philippines’ devalued currency, they had to spend more for imported items like fertilizer. Their income was dwindling, and a sudden medical emergency could mean disaster for their family. It was clear that the global economy was leaving Charing and Nario far behind.

Economic globalization—a reality or ideology?

When we think of globalization we often think of a world more interconnected due to advances in communication and transportation. Distinguishing economic globalization is more complicated because what is usually equated with globalization is actually an economic ideology called neo-liberalism. This ideology espouses small government, market-driven growth, and the removal of barriers to trade and investment. Everyone benefits from this kind of globalization, so the argument goes. But, in truth, it is primarily the corporations and capital investors who call the shots and make the gains. Some people therefore use the terms “corporate globalization” or “unregulated globalization” to indicate that other models of globalization are possible.

Most of us are beneficiaries of neo-liberal economic globalization. We can eat mangoes and strawberries in the middle of winter, buy T-shirts from Burma for a few dollars, replace last year’s laptop with a better and cheaper model this year, and invest in mutual funds that will ensure us a cozy retirement. Life looks pretty rosy from our perspective.

But the benefits of economic globalization are uneven. According to the United Nations Development Program, the disparity between the rich and poor is widening both within countries and between them. While the number of people living on less than $1 per day has fallen in the last decade, almost all of this improvement has happened in one country—China. Elsewhere, the number of people living in abject poverty has risen sharply. Globally, the richest 10 percent of the population accounts for 59 percent of the world’s wealth, whereas the poorest 40 percent, those who live on less than $2 a day, account for only 5 percent of global income.

Disparity in income is only one aspect of the shadow side of the global economy. Despite the benefits it provides, globalization contributes to the homogenization of culture, as Coca-Cola, McDonalds and Britney Spears replace the foods, music and traditions of local cultures. Globalization means increased harm for the natural environment, as natural resources are plundered and increasing amounts of fuel are used to transport goods around the world. Globalization undermines democracy as economic power is concentrated in the hands of corporations that are accountable only to their shareholders.

Another way

An old proverb says that if you give people a fish you feed them for a day; whereas if you teach them to fish you feed them for a lifetime. For many decades MCC, a Christian organization engaged in meeting human need, has sought to teach people to fish, among other things. But the realities of economic globalization demonstrate forcefully that the real problem is lack of access to the sea. The global poor know how to fish—but they need to be able to sell their fish and make a decent living. How can global and national economies be restructured in ways that the benefits are truly shared and that the “least of these”—as Jesus identified the poor in Matthew 25—are served?

Over a two-year period, MCC held a series of consultations with global partners on economic globalization. A key realization was that a major force driving the globalization system is the greed and unsustainable consumption patterns of those who already have too much. Our lifestyles support the systems that impoverish other members of our human community and desecrate God’s good creation.

Christians are called to practise justice and to live in ways that make God’s abundance available to everyone.