Canadian Mennonite

Volume 11, No. 01

January 8, 2007

Korean Anabaptist Fellowship in Canada launched

Calgary

|

Fifteen Korean Mennonite Church leaders from Toronto, Waterloo and London, Ont., Winnipeg and Vancouver had more than one good reason to travel to Calgary last fall. On Nov. 25, they celebrated the launch of an international partnership between Trinity Mennonite Church in Calgary and the Jesus Village Church in Chun Chon, South Korea.

The event, which included a banquet of Korean dishes such as kimchi, provided an opportunity to gather and discuss the formation of the Korean Anabaptist Fellowship in Canada.

A vision for the formation of the international fellowship began last January, when a number of Korean church leaders met at Charleswood Mennonite Church in Winnipeg.

Initial discussions were wide-ranging. Newly appointed fellowship coordinator Bock-Ki Kim of Toronto United Mennonite Church explains: “In January [2006], everything was unclear. We did lots of brainstorming about the name, and finally postponed that decision. When we met in Calgary, several brothers suggested that we discuss tangible things, such as where and how often to meet.”

The suggestion was helpful.

“This time, in Calgary, the discussion was narrower and deeper,” Kim says.

The group agreed on the name, appointed Kim to a three-year term as coordinator, and decided to meet annually at the Mennonite Church Canada assembly.

The Korean Mennonite Church is new to Canada, growing as a direct result of Korean students studying at Canadian Mennonite Bible College (now Canadian Mennonite University) beginning in the 1990s. Charleswood Mennonite Church, where many of these students attended, became the birthplace of the first Korean Mennonite congregation in Canada.

As an emerging church made up mainly of immigrants, Korean Anabaptists face some unique situations and issues.

Tim Froese, MC Canada Witness executive director of International Ministries and a former worker in Korea, notes, “Many of the Korean people have Presbyterian and Methodist backgrounds. One of the things we talked about [in Calgary] was the question of identity.”

Issues of Anabaptist and Mennonite identity, developing personal connections, communication, immigrant concerns, cultural adjustment, Christian education and evangelism are all on the agenda for the fledgling organization.

“Evangelism is a key issue,” Kim stresses. “The Mennonite focus on friendship evangelism takes a long time. We are working on how to understand mission and evangelism in a Mennonite context. We need to give what we have, particularly the gospel. We have a strong passion to share the gospel and the way of life.”

Froese sees MC Canada having a role in supporting the emerging fellowship, noting that Korean Anabaptists and churches are spread over a broad geographic area and do not necessarily know each other. “We can work to facilitate opportunities for Korean brothers and sisters to rub shoulders with each other and the larger church,” he says.

The next meeting of the Korean Anabaptist Fellowship in Canada will take place at the MC Canada Assembly in Abbottsford, B.C., in July.

Bridging cultural and racial divides in the pages of Intotemak

Winnipeg

For nearly 35 years, Neill and Edith von Gunten have been using a small, nearly invisible quarterly magazine called Intotemak to share aboriginal stories across cultures and races.

With only 1,300 subscriptions and about twice that many readers, this informal yet newsy publication also makes its way to about 100 homes in the United States and as far away as Hong Kong, Paraguay and Argentina.

It was in the Argentinean province of Formosa where Mennonite Mission Network workers Keith and Gretchen Kingsley stumbled across a copy of Intotemak. In its pages they learned about the 2006 bi-national Native Mennonite Assembly in Atmore, Ala., this past summer. (See “Learning the meaning of being one,” Oct. 30, pages 6 to 8.)

The Kingsleys realized that their ministry with the indigenous peoples of Argentina’s northern Chaco region had things in common with ministry in a North American aboriginal context. They eagerly signed up to attend the event—and when they got there, they met their old acquaintances, the von Guntens, who are now co-directors of Mennonite Church Canada’s Native Ministry.

“We grew up together in the same church and played basketball together as children in Berne, Ind.,” Neill reflects. “We had opportunities to catch up with each other and I found that we have so much in common.”

Crossing cultural borders has become a special ministry for the von Guntens. Much of what they have learned about cultural border crossings has come from walking alongside aboriginal people for more than 37 years.

“We were surprised to find out that [the Kingsleys] knew about us and our ministry in Canada through Intotemak,” Edith says. “This little newsletter has so much potential for breaking down the walls that separate us culturally.”

At the assembly, the von Guntens eagerly listened as the Kingsleys shared about their lives with the indigenous Toba people in Argentina.

“It was important to hear their stories and realize that we all come from small, struggling native churches, and to know that they understand,” says Neill.

And in the process the Kingsleys formed an immediate bond with North American aboriginals in attendance.

At the closing session, Steve Cheramie Risingsun, pastor of the host congregation, presented the Kingsleys with a wall hanging as a symbolic gift and blessing for them and their Toba brothers and sisters in Argentina.

The von Guntens muse about the possibilities for more such cross-cultural meetings among different worldwide aboriginal groups at the Mennonite World Conference sessions to be held in Paraguay in 2009.

“[Aboriginal] churches and communities have so much in common, and it would be such an encouragement to all of them if they could share and learn from each other,” says Neill.

In the meantime, the von Guntens will continue their ministry of bringing together aboriginal and non-native people in Canada and sharing their stories through Intotemak. When indigenous groups come together—in person or in the pages of Intotemak—to share common experiences, borders are erased, say the von Guntens, since sharing stories is an inherent way of bridging differences, passing on knowledge and building relationships.

Congolese Mennonites relieved at success of elections

Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo

|

Historic elections in the Democratic Republic of Congo culminated in the Dec. 6 inauguration of Joseph Kabila as the country’s first democratically elected president in more than 40 years.

Mennonites in the Democratic Republic of Congo are relieved that their country successfully held national elections in 2006, after decades of corrupt dictatorship and two recent wars. Like many Congolese, Congo’s roughly 200,000 Mennonites hope the elections will begin a new era for their country, according to Pascal Kulungu, a Mennonite Brethren lay leader in the country’s capital, Kinshasa.

Congo’s elections were held under a 2002 peace agreement that installed Joseph Kabila as the interim president. The elections were accompanied by fears of widespread violence between supporters of Kabila and those of his main rival, Jean-Pierre Bemba. While there were several violent episodes during the course of the elections, Bemba eventually conceded defeat and the elections concluded relatively peacefully.

“This is giving more strength and hope to the Congolese people, in seeing the way we have accepted the president,” Kulungu says.

Congolese Mennonite churches welcomed the elections and encouraged their members to vote and run for office.

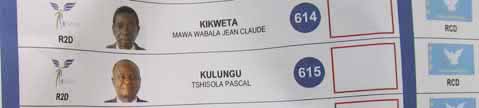

A total of 40 Congolese Mennonites ran for Parliament, and three were elected in a crowded field of more than 9,000 candidates, Kulungu says. Kulungu himself ran unsuccessfully in one of four Kinshasa ridings; he was listed as candidate No. 615 on page five of a six-page, poster-sized ballot with 854 other candidates running for 14 positions.

“This is the first time Mennonites have tried to be in the government,” he says. “We are satisfied to see that we have at least three people representing us.”

Mennonite Central Committee (MCC) helped organize Congolese and international election observers on election days in July, when the main election was held, and in late October, when a run-off vote between Kabila and Bemba took place. MCC also helped Congolese churches prepare their communities for the elections by organizing public meetings to explain the voting process.

|

The Manenga Mennonite Church actively prepared for the election this summer, according to Ray Dirks of Winnipeg, who was part of a Canadian delegation of July election observers.

The congregation got together on the last Saturday afternoon in July because it would not meet on Sunday, the day of the election. The church building is not much more than a few poles, tin sheets on half the roof, a tarp on most of the rest, and a blanket along one side to keep out the blistering sun.

Reverend Muenekuangu gave a powerful, wise and thoughtful sermon on selecting leaders who want to follow God’s will. He ended his sermon by imploring people to pray that night and vote the next day. In this very simple setting, it was obvious this tiny band of first-time voters were taking their impending role in potentially shaping the future of their country very seriously, Dirks says.

Kulungu now sees an acute need for reconciliation in Congo because of recent wars that turned neighbours and communities against each other. He says churches have a role to play in this process by teaching about nonviolent ways to resolve differences and to find healing following the elections.

“That is the challenge we have now—how people will reconcile with themselves, with their neighbours and with the country,” Kulungu says.