Canadian Mennonite

Volume 9, No. 03

February 7, 2005

We are proud to be members of a ‘peace church,’ observes this Mennonite theologian from Indonesia, but do we really know the full extent of God’s peace?

As members of the “historic peace churches,” we are often proud to be perceived by others as forerunners in peacebuilding. We feel honoured when, in the midst of so many conflicts and wars in the world, churches turn to us and ask for our wisdom.

Because of this heritage, we often assume that we understand the meaning of our claim to be peacemakers and its implications. But are we really aware of what it means to take our claim as peace churches seriously?

A careful look at the Bible shows us that peace has a wide variety of meanings. Peace is not simply the absence of war or the reduction of violence—though both are certainly involved. Peace also refers to well-being and material prosperity, made possible by the absence of the threat of war, disease or famine (Jeremiah 33:6, 9). Peace refers to just relationships between people and between nations (Isaiah 54:13-14). And peace refers to the moral integrity of a person who has no deceit, fault, or blame (Psalm 34:13-14).

Peace in the Bible is related to the wholeness of human beings and all creatures. It is related to the physical, relational and moral, as well as spiritual, dimensions of humankind. So as Christians we should not be satisfied just because there is no overt conflict or war around us. We may not have war in our context, but as long as there is economic, social or political oppression and exclusion, peace has not yet prevailed. We also may not have overt conflict with our neighbours, but as long as our life is full of deception and fault, we have no peace.

In short, as long as there are dimensions of biblical peace that do not exist, that can only mean peace has not prevailed in our life and context, and there is work we need to do in order to transform that condition.

John Warkentin, a Mennonite Brethren pastor in Wichita, Kansas, uses a peace continuum in his classes for new church members. The continuum extends from the individual’s peace with God to peace with one’s enemies.

In this continuum, the most important question to start with is whether we have peace with God (Romans 5:1). If so, peace then ripples out and begins to impact all our other relationships, including those in the family, workplace, and internationally. Peacebuilding always starts with peace with God.

But God, who is the source of peace, also wills peace for all creation. God wants us to move from peace with God to peace with our neighbours and, ultimately, with our enemies. We see this will of God very clearly in Jesus Christ, who demonstrated the way of peace through his life and ministry.

If on one pole of the continuum we find peace with God, on the other pole we find peace with enemies. This is indeed the most difficult peace to achieve. We may be at peace with God, but we may not be at peace with our enemies, especially enemies who have hurt us physically or emotionally. This explains why Christians who have been involved in bloody conflicts—such as those in Indonesia, Ireland, or South America—have difficulty reconciling themselves with people they perceive as their enemies.

Two disciplines

How can the church empower its members to work for peace? There are at least two basic disciplines that we need to consider to become peacemakers: the discipline of discernment, and the discipline of a radical Christ-like life.

When we commit ourselves to be peacebuilders, the first discipline in which we need to train ourselves is that of discernment. We need to be critical of the conditions around us to see whether all dimensions of peace are present. As Christians, we need to realize that our confession of the lordship of Christ is more than just an individual or sectarian choice. It is a claim about the cosmos.

In that confession we proclaim that there is no realm in the world that is not under the lordship of Christ; there is no dichotomy between Christ and culture, creation and redemption. There is no socio-economic-political realm that can be avoided by the church and left alone to be governed by its own values and norms. The whole world and all aspects of humankind are under the lordship of Christ. There is no exception.

This can only mean that, even though we are to have positive attitudes toward the world, we need clear criteria by which to judge whether an event is the work of God or the work of the devil; that is, whether it brings peace or evil. And it is in the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ that we get the criteria we need.

Thus, the church is the discerning community where we as Christians decide together God’s will for us and the world. When we see the meaning of Christ in a particular event, then we can confirm it. But when we do not see the meaning of Christ in that event, then we have to confront it.

Peacebuilding starts from the understanding of the character and will of Christ, not from the description of the reality of the world and our effort to fit the gospel into that reality. Even while we confess the incarnation of Christ, we have to realize that incarnation does not mean a blind ratification of all human activities.

Incarnation means that God has entered the world to show us what we can bind and what we have to loose (Matthew 18:18).

The second discipline we need to develop is that of a radical Christ-like life. We need to be aware that inside every person there is always capacity and limitation. Because we have capacity, we can develop ourselves and become creative. At the same time, because we have limitations, we need to be humble.

With the capacity we have, we can form ourselves to be peacebuilders if we want to. But because we have limitations, we should also discipline our wants that tend to bring us to things in contradiction to peace.

Developing a radical Christ-like life is not something that can be forced from outside, nor can it happen automatically. If we choose peace as our way of life, we have to do it voluntarily, without force. The way of life oriented to peace is not an obligation to be fulfilled because of external force. At the same time, we also have to discipline and train ourselves so that peace becomes our habit wherever we are, in all situations.

Individuals and structures

To help develop the radical Christ-like life that leads to the way of peace, the church must work with both individuals and structures:

• Individuals: We need to think seriously about how we can shape individual character so that Christians can become peacebuilders through social practices in the church. For example, we need to reevaluate the material we use in classes for new church members, to see whether it will equip new members with the insights and skills necessary for peacebuilding. By the same token, we need to reconsider our Sunday school material to see whether we have equipped church members—adults and children alike—to live out a peaceful way of life.

So with our worship. We need to re-examine whether we have made peace central in our worship. If we have many occasions in the church calendar to address various issues, such as mission month, family month or ecumenical Sunday, we need to ask whether we also have peace month or peace Sunday. And how about prayer and fasting for peace? Or a pilgrimage for peace?

We need to train our pastors, elders, deacons and all church members with the insights and skills for nonviolent conflict transformation. We need to struggle together with biblical texts related to peace and to design curricula for peace education in the church and in our Christian schools.

• Structures: Besides empowering individuals, we also need to work with our structures. Here we need to think, for instance, whether we have intentionally established a mechanism in the church to solve the conflicts that emerge inside and outside the church. Many churches that do not have such a mechanism only accumulate conflict. It then becomes a time bomb that eventually tears apart the whole church.

We also need to take a closer look at our church organizational structure. If we have a youth committee, women’s committee, mission committee or worship committee, we need to ask whether our church also has a peace committee in charge of educating and training our church members for peacebuilding inside and outside the church. Committee members could also function as mediators to transform conflict nonviolently in the church and society.

For us who are members of the historic peace churches, there is much work we need to do for peace. Some will be difficult and demand high commitment from us. Some is ordinary work that we are able to do in our everyday life. Whatever the situation we are facing, peacebuilding is not simply a dream. It is a concrete vision that we need to strive for as long as we claim to be Christians.

Then justice and truth have met together; righteousness (justice) and peace have kissed each other (Psalm 85:10).—Paulus S. Widjaja

The writer teaches theology at Duta Wacana Christian University in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. He also serves as secretary of Mennonite World Conference’s Peace Council. This article first appeared in The Courier.

A series on peacemaking

This issue concludes a two-part series of personal reflections about peacemaking. For previous stories, see January 24 issue.

This issue concludes a two-part series of personal reflections about peacemaking. For previous stories, see January 24 issue.

Conscientious objectors share their stories

As the world remembered the 60th anniversary of the liberation of the infamous Auschwitz concentration camp last month, four Mennonite men met in the home of Norman and Sue Weber in Elmira, Ontario, to tell their stories of being conscientious objectors (COs) during World War II.

“My parents taught us not to be involved with soldiers,” said Oscar Martin, who attends the Waterloo-Markham Meetinghouse in Elmira of his reason for refusing military service.

|

| Mennonite conscientious objectors during World War II: Clayton R. Shantz, Henry Martin, Oscar Martin and Norman Weber. |

|

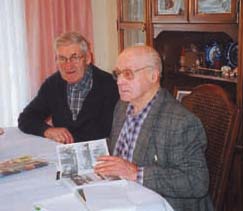

(left) Norm Weber and Oscar Martin recall their CO experiences of 60 years ago.

Henry Martin and Morgan Baer (right) |

|

Defying the law

Last summer I committed a federal crime. When I turned 18 and was required to register with the Selective Service System, I did not do so.

Failing to register is a criminal act punishable by up to five years in prison and a $250,000 fine. I am willing to be prosecuted but do not expect it. The primary punishment has been the withholding of financial aid for college.

Registration is a prerequisite to the draft and therefore intended to facilitate war. If I registered I would be considered a war asset because there is no option for conscientious objectors on the registration form.

I wouldn’t want my compliance or silence to imply my consent with the war machine that endorses killing as a solution. Instead of joining the military, I’d be willing to go to the Middle East to engage in nonviolent mediation and direct action.

Ultimately, my objection to registering stems from my allegiance to God and Jesus Christ. When choosing between inflicting suffering upon others or taking it upon myself, I strive to follow the way of Jesus.

I’m committed to pursuing peaceful solutions. In doing that I’d be willing to die, but not to kill.—Jason Shenk

The writer is from Goshen, Indiana.

Sometimes peacemaking feels 'like sand in the mouth'

I grew up in the pacifist Mennonite tradition, attending Springridge Mennonite Church in Pincher Creek, Alberta. In the back of my mind I was always interested in the peace side of my church tradition, but it wasn’t until I graduated with an engineering degree that I started to think about how peacemaking was a part of living my faith as well.

I joined a Mennonite Central Committee Work and Learn Tour to El Salvador in 2001, and in learning about that country’s conflict-ridden history, I started to think more about what Mennonites might be doing to actively reduce violence around the world.

I discovered Christian Peacemaker Teams (CPT) through the Mennonite Church Canada website, and decided to go on a CPT delegation to learn more about this organization. While on a CPT trip to Colombia I was drawn to CPT’s spiritually-based, intentional-community style of being a presence in a conflict situation and actively working to “get in the way” of violence.

After some time back home in Calgary thinking and praying about what I was to do with this experience, I decided to quit my job as a computer programmer and join CPT full time. I participated in the month-long CPT training in January 2003 and committed myself to three years working full-time with CPT. I spend about two-thirds of each year working on a CPT project, and the times in between speaking about my CPT experiences, as well as resting.

Soon after training I joined the team in Hebron, where we provide a presence for the civilian population, and work with Palestinian and Israeli peace groups to reduce the violence that is a result of the military occupation of the Palestinian Territories.

You may have read about the two attacks on CPT members near Hebron by masked Israeli settlers while we were accompanying Palestinian children from their village to the village where their school is located (Oct. 18, page 23). Maybe your question is: What in the world is CPT still doing there if it is not safe?

My simple answer is that as CPT members we are aware that violent acts might be committed against us; however, this doesn’t stop us from getting in the way of violence. But we do not “seek” violence. We have many discussions about situations, our actions, and what might happen. As foreigners, we have the choice to leave. Who stays behind if we do that? People who cannot leave and who are without witnesses from outside who can spread their stories to the world.

One CPT trainer says our situation often feels “like sand in the mouth.” While I believe that God is calling me to work with CPT right now, I get scared and intimidated. The natural reaction is to retreat and go to a safe place. Going beyond this fear takes prayer and convincing by your inner self, and it tastes like sand in the mouth.

It’s going out the next morning after being attacked and walking through the same hills with the school children. It’s talking with the Israeli soldiers who stop you and tell you they cannot provide for your safety if you go with the children.

The strength for doing this work comes from many different places. The strength comes from following the example of Jesus in showing another way to respond to violence. The strength comes from knowing that my friends, family and church respect my calling to this work and support me financially, through prayer, and in showing interest in my work.

And the strength comes from remembering that there are many other people in history who have worked nonviolently towards peace, and that there are still more working today all over the world.—Diane Janzen

My journey toward peacemaking

The Anabaptist reformation started in the 1500s and in 1954, and in every year between and since, I suspect.

In 1954, my father was the pastor of a small Baptist church in Arizona. When I was five, my father asked me if I wanted to follow Jesus in entering the waters of baptism. God, however, impressed it upon me that this was not what he wanted me to do at that time. In this way God began the Anabaptist reformation in my life.

When my best friends were sent to fight in Vietnam, I began to meditate on the saying of Jesus, “My kingdom is not of this world. If it were my servants would fight.” My mother pleaded with me to apply for conscientious objector (CO) status.

Long before the war, I had been certain that God’s plans would take me to Canada. For me, the draft was getting in the way of seeking the kingdom of God’s Messiah and his righteousness.

In the essay required for my CO application, I asked: Can the army provide me an opportunity to serve the work that the Prince of Peace began in the world? I sat before a panel of men who looked like ex-marines.

The one with my file asked in a quiet, angry voice, “Did you write this essay?”

“Yes,” I said. He pointed and said, “There is the door.”

Another man asked, “Are you a Jehovah’s Witness or a Quaker?”

“I am a Baptist,” I said. The panel coldly dismissed me without a further word.

My parents seemed to believe in the logic of the Cold War. My father, a veteran himself, reminded me that my mother’s first husband died liberating France. “Had we not fought the Germans,” he said, “all the Jews in the world would have been exterminated.”

“If great armies of people were willing to give their lives fighting against the causes of war, instead of for them,” I responded, “perhaps that war and the Holocaust never would have happened.” I had never heard of Mennonites or Anabaptists, but the Anabaptist reformation was blazing in my heart.

Once in Canada I sought people who were looking for a civilization whose saviour was not the nuclear bomb. It was no easier in Canada for young radical idealists to find work than it was in the United States. I picked a plant from the forest used by florists for about 25 cents an hour, and ate discarded produce from behind supermarkets. I could not get welfare for five years.

Living in the world of Canadian poverty I learned about the deep relationship between broken-spirited people and the Gospel. I was baptized in my early 20s in the Georgia Strait off B.C.’s Sunshine Coast. Some years later, I attended Northwest Baptist Theological Seminary, searching desperately for a language of the Gospel of peace that could meet the need of the severely damaged people I was working with.

My search took me into the early centuries of the Free Church movement, then to the Anabaptist Reformation. It was only a matter of time before my family and I found Emmanuel Mennonite Church in Abbotsford and made it our home church.

Now in my middle years I understand that the way God overturned the process of baptism in my life was a message about the nature of his upside down kingdom. Our greatest witness to peace is our own adult repentance. Because of this, I do not labour for a gospel that simply helps those who are good at helping themselves. I seek to serve the Messiah about whom Mary sang: “The powerful he makes to stand aside. He lifts the poor up out of the ditch; he fills the hungry spirit with his own goods. For those who are satiated with wealth he has no gift.”

On my journey toward peacemaking I have learned one thing: When the world-wide vote for peace is finally held, they shall say, Peace! Peace! But there shall be no peace. But when the poorest spirits throughout the world are helped to understand the Good News as Mary did, and rejoice with her that the salvation of Israel is come despite all human failings, then world peace will truly have come.

For me, Mary’s anthem is the true conscientious objection to the true cause of all violence, and this is the fire that burns at the core of the Anabaptist reformation which will never be quenched.—Max Kirk

The writer is a mediator in private practice in British Columbia.

Copyright © Canadian Mennonite. To reprint articles or photos, please contact reprints@canadianmennonite.org. To contact our office or staff, please see our contacts page.