Canadian Mennonite

Volume 8, No. 22

November 15, 2004

B.C. churches talk and learn about homosexuality

Abbotsford, B.C.

More than 100 people gathered at Emmanuel Mennonite Church here at the end of October to begin a journey of learning, listening and getting to understand each other better on the subject of homosexuality.

“Walking in Grace” was the first of two conferences set up by a Mennonite Church B.C. committee intended to bring people together to minister to one another “as we strive for greater biblical understanding of homosexuality.”

Participants were assigned to tables where they shared what they hoped to gain from the weekend. Some expressed ambivalence and impatience with the process, while others hoped the weekend would lead to greater understanding.

The conference included testimonies from Neil Klassen and Toni Dolfo-Smith from Living Waters, an organization that deals with “relational and sexual brokenness.” Both men were in same-sex relationships in the past; Klassen is now celibate while Dolfo-Smith is married with children.

Dolfo-Smith emphasized what the church should not do.

“Do not pretend that sexual problems don’t exist in the church…stop attacking the integrity of homosexuals…don’t confuse gay extremists with all homosexuals…don’t use clichés or subtle jokes,” he said. “Don’t say ‘love the sinner but hate the sin’ because for most of us, we don’t really love the sinner.”

What the church can do, he said, is speak from facts rather than rhetoric, admit the mistakes that the church has made, be clear in its beliefs, be honest about limitations.

“What does work is when we exhibit the compassion of Christ and walk with people in their journey,” he said.

Willard Swartley from Associated Mennonite Biblical Seminary, author of Homosexuality: Biblical Interpretation and Moral Discernment, led several sessions on biblical interpretation, culture and discernment.

“How our church confronts this issue in today’s society is important,” he said, adding that God calls us to be his ambassadors but also to welcome all people.

The story-telling and teaching were interspersed with time for questions and discussion. Participants were asked how they would respond if their best friend revealed that he or she was homosexual. Some confessed that they would feel a great deal of discomfort.

“I don’t personally know anyone who is gay,” one participant said, “but I hope that I would be able to stay friends with someone who shared this with me.”

One table reported, “We said that we wouldn’t make sexuality the main identifier of who we are and would find a way to affirm our relationship, show kindness, grace and mercy without condoning the practice of homosexuality.”

After Swartley’s discussion on discernment, one participant responded with great emotion. “It feels like we’re talking more about sin than about grace,” he said. “In light of the fact that there is so much we don’t know; we do know that we need to recognize that we are all sinners and sin is not just a matter of action. We are redeemed by grace.”

Swartley responded by saying that the church shouldn’t avoid the confession of sin. “We must each confess our sin, but we do not have an excuse to continue in it,” he said.

As the day came to a close, four “listeners” reported what they had heard. They heard that the discussion should not focus on homosexuality but on sexuality and the whole range of human brokenness. They reported a need for balance and a willingness to be transparent and to change.

Sven Eriksson, denominational minister for Mennonite Church Canada and one of the listeners, appreciated the level of vulnerability and trust that he experienced. Instead of division, he saw honest efforts to listen and learn.

“This is an event that has generated more light than heat,” he said. “Praise be to God.—Angelika Dawson

Reflections on a journey to Ethiopia

The son of Mennonite missionaries, Byron Rempel-Burkholder spent his childhood in Ethiopia. The following is from reports of a recent visit.

This summer, our family of four detached itself from its middle class existence in Winnipeg and set up house in Addis Ababa, capital of Ethiopia.

| The Rempel-Burkholder family in Ethiopia. |

An overarching purpose, however, was to learn about life and faith in the southern hemisphere. By economic statistics, Ethiopia is the third poorest country in the world, but it’s one of the richest in cultural and religious heritage. We wanted to see what God is doing in the Meserete Kristos Church (MKC), the fifth largest denomination in the Mennonite World Conference.

The MKC was in its infancy in the 1950s and 60s when my parents served with Eastern Mennonite Missions in eastern Ethiopia. Today, with about 250,000 worshippers on a given Sunday, the MKC is the fourth largest Protestant denomination in the country. In the 1960s, worship reflected the gentle piety of the missionaries; today, the energetic music, emotional prayers, and earnest preaching display a home-grown movement of the Spirit.

The main motifs of what we saw were evangelistic fervour, charismatic gifts, rigorous discipleship, and intense prayer. The way these are lived out in the MKC is not perfect, as leaders willingly admit. It will take some time for me to figure out how the energy and vision of the MKC might be applied to my life and church in Canada. Nevertheless, I found myself inspired and renewed by what I saw.

Rapid growth

We had lunch one day with acting general secretary Kena Dula and evangelism director Tefera Bekere. Melita and I expressed admiration for MKC’s growth statistics: 10.6 percent during 2002-2003.

We were startled by Teferea’s response: “We are embarassed by that…. A few years ago it was close to 30 percent.” We knew about the rapid growth during the persecution of the Marxist era (1974-1991), but 10.6 percent still seemed strong to us, compared to growth of the church in North America.

Today, the number of baptized members is 120,667, plus another 42,000 in baptismal instruction, and 81,000 children. They worship in 335 churches and about 700 church plants.

It is a given in the MKC that evangelism is the central task of the church. Congregations appoint lay people to their “great commission” committees. The annual assemblies in the MKC’s 16 regions spend chunks of time in examining growth statistics and how to reach more people.

Tefera’s office is responsible to support evangelists in areas that are beyond the reach of local congregations. Today there are 93 such missionaries on the border of Sudan, and in neighouring Eritrea, Djibouti and Somalia.

Charismatic Anabaptists

Worship at the Bole Airport congregation in Addis Ababa. In 1982, the Marxist government, worried about the large crowds one congregation in this city was attracting, shut down the Meserete Kristos Church and imprisoned six of its leaders. When the MKC re-opened eight years later, it had grown ten-fold.

Possibly the hardest thing for us to get used to was the loud and emotional worship. A typical Sunday service begins with a long prayer time in which worshippers raise hands and pray out loud—often crying out, sometimes in tongues. Some hand motions dramatize the repelling of the forces of evil.

Preaching, like the song-leading, is heavily miked and animated. “Signs and wonders” are also part of the church culture. We saw a preacher order demons out of two women, who fled screaming out of the sanctuary, with deacons following.

Congregational singing is led by robed choirs or music teams, and accompanied by a synthesizer with canned percussion and occasionally drums—all cranked up to a formidable volume. Sung in the pentatonic scale, the songs are quite moving, mainly because of the heartfelt emotion of the singers.

It’s a far cry from the services I knew on the mission station 40 years ago. Then we sang Amharic translations of gospel songs, such as “Amazing grace.” The only song I recognized this summer was an adaptation of “I have decided to follow Jesus.”

MKC worship takes the Holy Spirit seriously and expects displays of God’s power. Its charismatic theology took root in the late 1960s out of the “Heavenly Sunshine” renewal movement. The energy of that movement during the Marxist years caused the government to close the church in 1982. The educational and medical institutions the mission had established were nationalized, including the hospital at Deder where my parents worked.

Despite continued partnership with Eastern Mennonite Missions and Mennonite Central Committee, the early missionary era today is a respected but increasingly remote memory in the MKC. Church plants are supported by local funds and a variety of foreign groups, including German Mennonites and the Pentecostal Assemblies of Canada.

Mulugeta Zewdie, newly-elected general secretary of the MKC, believes that when religious values come to be considered “matters of opinion, personal preference or subjective choice rather than objective [reality]” the church loses its evangelistic power. This is a danger in the Ethiopian church as its society is influenced by Western culture.

For Mulugeta, the church must stay rooted in the example of the early church whose strong community life, devotion to the Bible, Christ-like character and demonstrations of God’s power all worked together to spread the gospel.

“Today, missionaries in the younger churches of Africa and Asia are convinced of the reality of exorcism and the power of healing in the name of Jesus,” says Mulugeta.

Mulugeta also recognizes that MKC may be called to a greater “biblical balance” in which salvation is understood to include “justice, and the liberation of the forgotten and the poor—a response to misery, chaos, fear and the brutality of community life.”

Drop in at the MKC college on a Friday and you will find no classes, because this is a day of prayer and fasting. The chapel is a buzz of students kneeling on cushions and praying out loud. They stay for hours.

Even so, leaders complain that the level of spiritual energy is not what it should be. Hailu Chernet, dean of the college, remembers the intense fasting and exorcisms that were so common during the Marxist era.

Today, he prays for persecution to return so that the church can recover the intensity of the Spirit’s movement.

Growth pains and training

Perhaps fuelling the sense of “cooling” in the church has been some recent growth pains. At the national level, the church has just come through a conflict over division of authority in church programs.

Congregations are questioning leadership structures that served well during the time of persecution but may not work so well today. Part of that struggle revolves around how much authority elders, pastors and evangelists should have in the congregation.

According to Zewdie, the key to keeping the spiritual fires alive is leadership training. “In order to evangelize and attain sustainable church growth, MKC needs an effective strategy in the area of leadership training. Members are expected to be rooted in the word of God and equipped for ministry.”

Fortunately, the MKC has assets to meet this challenge. Probably the greatest legacy the missionaries bestowed was the empowerment of Ethiopian leaders.

Within five years of legal incorporation in 1959, missionaries handed over the top positions to Ethiopian Christians. The Nazareth Bible Academy trained leaders locally and many were sponsored to attend American colleges.

According to Bedru Hussein, past vice-president of Mennonite World Conference and currently an administrator at the MKC College, the foresight of Eastern Mennonite Missions “has given leaders the authority to lead today. That did not happen with other denominations.”

Training happens on two tracks. Teaching seminars organized by the MKC head office are held semi-annually in each of the MKC’s 17 regions. The pastors and teachers who attend then teach their congregations. Curriculum ranges from Bible study to issues in church and society.

The MKC College, begun in 1994, has three diploma and degree tracks, with an enrolment this year of 105 students. The curriculum has been expanding from a strictly theological and biblical focus to include subjects that will enable students to work and witness in the world of business.

A quarter of the college’s students come from other denominations. Last year the school graduated 55 students. Its biggest project is a $3.5 million campus in Debre Zeit, just east of Addis Ababa. Construction began last summer, even though half of the money had yet to be raised.

A smaller training institute is being built in western Ethiopia—the Wollega Bible College.

The MKC is also involved in development work, such as AIDS orphans’ education and prison ministry, but always in connection with evangelistic outreach. The prison ministry has established congregations in 33 prisons during the last three years.

Ministry cannot be “holistic” unless people hear the word of God and join the church, says Kibatu Retta, education coordinator for MKC’s Relief and Development Association. For example, when church workers delivered MCC food and reforestation aid in the Boricha region two years ago, they preached in their off hours. Since then, almost 800 people have been baptized.—Byron Rempel-Burkholder

The writer, from Winnipeg, is an editor with Faith & Life Resources, a division of Mennonite Publishing Network.

Origins of the Meserete Kristos Church

| Mulugeta Zewdie was elected in August as General Secretary of the Meserete Kristos Church in Ethiopia. |

Through clinics, schools, two hospitals and the Nazareth Bible Academy, a network of believers came into being. Many of these had been nominal members of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church; a few had been Muslim. (Orthodox comprise 40 percent of the Ethiopian population, Muslims 35 percent.)

The Meserete Kristos (Christ the Foundation) Church was incorporated in 1959.

In the 1960s, a grassroots movement named Semay Berhan (Heavenly Sunshine) sprang up in Nazareth, with members experiencing dramatic manifestations of the Spirit—healings, exorcisms, speaking in tongues and a zeal to share the gospel. Many members joined the MKC, planting seeds for the charismatic theology and worship style that is now standard.

Despite the Marxist revolution in 1974 and growing restrictions, the church continued to grow. Then came the era of persecution. In 1982, worried by the large crowds that the church in Addis Ababa was attracting, the government closed the MKC and imprisoned six of its top leaders.

The church met secretly in house groups, trained leaders and published teaching materials. Some missionaries stayed on as workers in government or other organizations.

When the regime fell in 1991 and the churches were re-opened, the MKC had grown tenfold—from 5,000 to 50,000 baptized members. The dramatic story of the MKC is told in Beyond Our Prayers by Nathan Hege (Herald Press, 1998).

Today, the MKC continues to welcome support from the global Mennonite church. Eastern Mennonite Missions and MCC channel funds and some staff through the Mennonite Mission in Ethiopia, managed by John and Holly Yoder Blosser.

Carl and Vera Hansen of EMM do teaching and fundraising for the MKC College. Other North Americans also occasionally teach there.—From report by Byron Rempel-Burkholder

| Solomon Gebreyes befriends Getasew, a boy whose father is doing a life term for murder. |

Service celebrates Ukrainian-Mennonite experience

Tokmak, Ukraine

A new choral work by a Canadian composer and a Ukrainian choir singing music from the Orthodox tradition were both part of the Molochna Bicentennial Thanksgiving Service here on October 10.

|

| Larry Nickel’s composition, “Molochna Thanksgiving,” was premiered at the bicentennial worship service in Ukraine, on October 10. Nickel has taught music at Mennonite Educational Institute in B.C. for many years and in 1993 won an international award for his “outstanding service to jazz education.” He is co-founder of the West Coast Mennonite Chamber Choir which has recorded many of his compositions. See back for more on music in Ukraine. |

About 550 people attended the service, including 191 passengers on the Mennonite Heritage Cruise. Also participating was a group of Russian emigrants now living in Germany (Aussiedler), and members of four local congregations.

This was the largest gathering of Mennonites in Ukraine since 1943, according to Walter Unger, co-director of the heritage cruise and an initiator of the celebration.

The service opened with a new work by Larry Nickel of British Columbia, “Molochna Thanksgiving,” for choir, baritone solo, instruments and congregation. The work included “new realizations” of German hymns such as Ich bete an die Macht der Liebe and So lange Jesus bleibt der Herr.

Diana Wiens of Edmonton conducted the work; her husband, Harold Wiens, was the baritone soloist. Instrumentalists included Calvin Dyck, violin, and Betty Suderman, piano, both from British Columbia.

Local Mennonite congregations gave presentations in words and music.

In his presentation, “Reflections on the past: Look to the Rock,” Rudy Wiebe walked through Mennonite history, from sixteenth century Europe to the diaspora of Russian Mennonites in the twentieth century.

“But today we can meet,” he said. “We can come together and tell each other our stories, however sad or happy or amazingly miraculous they may be. That is the most beautiful thing

we human beings can do…not yell at each other, or quarrel about land, or kill one another because of an idea, or—worse—kill because of God. No!…

“We tell each other stories, as, by his gentle example, Jesus himself taught us. Our past gives us the stories by which we can live our present.” Wiebe ended with his own story—his parents were the only members of their families to get out of Russia in the dramatic “Flight over Moscow” in 1929.

In his “Thoughts about the future,” Paul Toews reflected on how things have changed since he first visited the Soviet Union in 1989. Acknowledging the difficulties that continue, Toews focused on the hope of the present.

“Today there are four Mennonite congregations in Ukraine—Zaporizhzhia, Kherson, Kutuzovka and Balkova. Today Ukrainians and people from various countries are working together in effective partnerships in the work of the Mennonite Centre in Molochansk, in the work of the Mennonite Family Centre in Zaporizhzhia, in the work of Mennonite Central Committee, in the work of the Baptist Union….

“Today we meet with a sense of hope, with a sense that a Mennonite presence and witness in Ukraine is growing and is making a difference.”

Toews referred to the monuments that were unveiled in spring to commemorate the 200-year history of Mennonites in the region and quoted the Ukrainian mayor’s comments at that event: “We want to carry into the future the values that you [Mennonites] taught us, the legacy that you left to us…. We thank you for helping us to recover it. With your help we want it to shape our future.”

The benediction to the anniversary service was spoken by Alan Peters from the USA and Zoya Gerasimenko of Zaporizhzhia.

In the afternoon, many enjoyed a program of music and other events in Halbstadt/Molochansk. Some attended the opening of a memorial to agricultural innovator and leader Johann Cornies in Juschanlee (now Kirovo).—Compiled by Margaret Loewen Reimer

Canadian musicians make music in Ukraine

British Columbia musicians Calvin Dyck and Betty Suderman provided mus ical resources for the Mennonite Heritage Cruise to Ukraine this fall for the second time, and performed for Ukrainian audiences in several places.

ical resources for the Mennonite Heritage Cruise to Ukraine this fall for the second time, and performed for Ukrainian audiences in several places.

They gave their theme recital, “Golden violin,” at Melitopol, Tokmak and Zaporizhzhe. The recital, with costumes and historical anecdotes, traces the history of Dyck’s violin, crafted in 1807 by Johannes Cuypers of the Netherlands. Suderman is a pianist.

Dyck and Suderman also gave master classes and performed with the student orchestra at the Zaporizhzhe College of Music. They presented Kernlieder (core Mennonite hymns) at Melitopol Pedagogical University and performed at the Tokmak College of Music (near Halbstadt in the former Molochna settlement).

Their major concert for the cruise passengers was held in Sevastopol, Crimea in the hall of the Black Sea Fleet Ensemble.—From report by Walter Unger

Mennonite historians address the state of their art

Winnipeg, Man.

The writers of an upcoming one- volume history of Mennonites in North America asked for—and got—plenty of advice at a “State of the art of North American Mennonite history” conference here October 1-2.

|

| Barbara Nkala speaks with John Lapp after their presentations. |

|

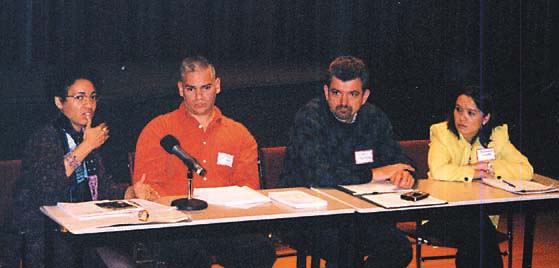

| The panel on race and ethnicity included, from left, Malinda Berry of Union Theological Seminary in New York, Donovan Jacobs of MCC Manitoba, Juan Martinez of Fuller Theological Seminary in California, and Stephanie Phetsamay Stobbe of Menno Simons College in Winnipeg. |

Heard at the history conference

What does it mean for us to read about Mennonites of all cultures and thereby gain an understanding about what being Mennonite means? asked Malinda Berry, who is African-American, at the conference on North American Mennonite history.

“Would Patrick Friesen [a poet mentioned in the Mennonite literature session] recognize me as a Mennonite on the streets of New York?” she asked. What about the segregation of races during footwashing and communion—have those rifts been repaired? “We still need to transform our history,” she concluded.

Others added their observations about the complexities of writing a North American Mennonite history.

Donovan Jacobs, who works with native ministries in Manitoba, wondered why there are only two small “associated” native Mennonite churches in Mennonite Church Canada after 45 years of mission work. “My concern is not with the missionaries who walked with the people…but with the many who did not. How do we work at relationships?”

What is Latino Mennonite identity, given that the mission strategy was acculturation? asked Juan Martinez from California.

“Much remains to be done,” noted John Lapp in his keynote address. “Just as we historians need to develop and accommodate to new perspectives, so does the entire church. We are beginning to see church agencies talk about ‘repositioning’ themselves for the new situation…. How will priorities change? How will resources be reallocated?… Can our definitions of evangelism be reformulated?…

“If we as historians of the church have a ministry it will be to highlight this new church history and to help our congregations and conferences, mission and service agencies, colleges, seminaries and even retirement communities think about their work in new ways.”

One conference attender was struck by how the younger generation is pushing the boundaries, especially in the Peace and Justice session. A highlight for her were presentations by Rachel Waltner Goossen, Washburn University in Kansas, and, Janis Thiessen, University of New Brunswick.

Waltner Goossen spoke about the broadening of Mennonite peacemaking from objection to military service to daily life. The women’s movement helped to raise issues of domestic violence and sexual abuse. The increased focus on conflict transformation is being incorporated into art, music and literature, noted this participant.

Thiessen shared her conclusions from studying Mennonite labour history and class. Athough we have discussed power and authority in the church, little has been done with labour-management issues, she said.

“I found the conference stimulating as a whole,” said Dan Nighswander, general secretary of Mennonite Church Canada. “What difference does it make that we are ‘Canadian’ Mennonites? This conference pointed us in the direction of looking for some answers to that.”

Henry Krause, moderator of MC Canada, also found himself challenged for his work in the church. One issue is our connection to the global Mennonite church, he said. He wondered what we as Canadians can contribute and what we can learn from our history and the history of Mennonites on other continents.

Another challenge is thinking about identity in a Canadian context, and “the connection between ethnicity and being a missional church.” The variety of topics “stretched my own thinking about what we are about as Mennonite Church Canada and the tensions that we wrestle with as a church in this time,” said Krause.

Many of the presentations will be published in the Journal of Mennonite Studies.—From report by Leona Dueck Penner

North American diversity challenges historians

The conference on North American Mennonite history at the University of Winnipeg in October demonstrated that the diversity of influences, experiences and theological directions within the North American Mennonite community will be difficult to capture in a single volume.

The diversity is at two levels—within Mennonite groups, and between Mennonite groups in the U.S. and Canada.

Within groups such as Mennonite Church Canada, diversity is reflected in theological influences (evangelicalism, Benderian Anabaptism, activist Anabaptism, liturgical renewal), Christian expression (emphasis on community relationships or on correct doctrine), worship styles (praise music, worship bands, hymnal-only, choirs), ethnic/cultural/immigration/language background (European, Indigenous, Asian), economic status, environmental context (urban, suburban, small town, rural), congregational size, and more.

Even within smaller groups, conference participants heard of startling diversity—the Old Colony Mennonites in Manitoba divided only last year over keeping the German language in worship.

Few presentations attempted a comparison between Mennonites in the U.S. and Canada, but helpful insights did emerge. Except for the Amish, U.S. Mennonites have not been labelled as an “ethnic” group for many years. This contrasts with Canadian multiculturalism that has encouraged an ethnic-religious self-understanding.

This self-understanding has influenced the way Canadian Mennonites relate to new Mennonites from non-European cultural streams, and reflects why Canadian Mennonite literary works sometimes reflect an ethnic, but not religious, ethos, in contrast to most “Mennonite” writers in the U.S.

This diversity between the national churches certainly warrants greater study, given the shift of the largest denominations (Mennonite Church and Mennonite Brethren) into national structures.

Nonetheless, the time for a new North American Mennonite survey history is here. Both the Mennonites in Canada series and the Mennonite Experience in America series did not extend much beyond 1970.

The impact of recent gender and family analysis requires greater integration into Mennonite self-understanding, as does the emergence of many non-European voices within the North American Mennonite world that seek to integrate their faith with their cultural context.—Sam Steiner

The writer is librarian and archivist at Conrad Grebel University College in Ontario.