Volume 7, number 21

November 3, 2003

The myth of redemptive violence

Why are we so attracted to violence as a solution to evil? asks Sue Steiner in this second in a series for Peace Sunday.

When I was about 10 years old, I sat glued to our friends’ television set every Saturday night. We didn’t have a TV in our own home, so we went to my parents’ friends’ house every Saturday because they watched the Lawrence Welk Show.

And after Lawrence Welk was over, I waited for these words: “Why don’t we stay and watch Gunsmoke?”

Gunsmoke began in 1955 and lasted for 20 years, the longest-running dramatic series in the history of TV. Gunsmoke started a trend for TV westerns and outlasted them all.

Here’s the formula. You have a frontier town named Dodge City. You have a shapely woman named Miss Kitty who runs the Long Branch Saloon and we’re not sure what else. You have a tall, lanky U.S. marshall named Matt Dillon who roams the territory in the line of duty with his hillbilly deputy, Festus.

In Dodge City, peace is always tenuous. Each week, Marshall Dillon has to contend with cattle rustlers, fugitives, stagecoach bandits or perhaps a gunslinger. He prefers to take such folks into custody for a fair trial. But those who resist may well end up at Percy Crump’s—Dodge City’s undertaker and furniture dealer.

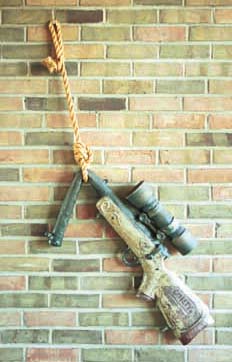

The most exciting part of Gunsmoke is, of course, the gunfight. A fugitive from justice wanders into Dodge City—perhaps into the saloon. You can feel the excitement build. Marshall Dillon invites the guy outside for a gunfight. The street is cleared.

Of course the bad guy draws his gun first. But Marshall Dillon is always faster and calmer, and peace is restored to Dodge City…until next week.

Now why would Christian pacifists take their little girl to watch Gunsmoke every Saturday night? Why would they instill in her the myth of redemptive violence? And why would this little girl be so excited and oddly comforted by it?

The “myth of redemptive violence” is a phrase coined by Walter Wink, an American New Testament teacher. Wink claims that most cultures have a creation story about how their society began and that story becomes part of the culture’s DNA. Almost always, this plotline features a struggle between the forces of evil (other folks) and the forces of good (us, of course).

The odds are stacked in favour of the evildoers because they cheat, lie and use brute violence. By contrast, our deepest qualities are goodness, decency, honesty and compassion. And at some point—just as the forces of evil are about to prevail—the powers of good find themselves compelled, against their wishes, to respond to evil with brutal violence of their own.

Of course, this is a righteous violence, a redemptive violence that is swift and furious in its outcome. It’s a violence that is necessary if goodness is to prevail. Afterwards, we get on with the civilized ideals of truth and justice.

Dominant religion

Wink claims that the dominant religion in most societies today is not Christianity or Judaism or Islam, but the myth of redemptive violence. It has provided the rationale for every war in the history of the United States, including, most certainly, the one against Saddam Hussein.

It’s the subplot of virtually all martial arts and action movies, many Saturday morning cartoons, and all westerns. It reveals our basic assumptions about the nature of reality and often operates at a deeply subconscious level.

If we are pacifists but also realists, we may well believe that at the end of the day the power of the fist or the gun or the bomb really is the universal solvent.

This worldview is very compelling, says Mennonite historian John Roth in Choosing Against War (Good Books, 2002). But there are a couple of problems. The first problem—which no one seems to notice—is that “redemptive violence” never permanently takes care of things. Marshall Dillon will be back next week. And after Saddam Hussein, another gunslinger will enter Dodge City.

So the cycle of violence continues. But for Christians, there’s an even more serious problem—God is virtually irrelevant. Who needs God when we have Matt Dillon and George W. Bush to look after things?

There is another worldview, one that depends utterly on God. There is another plotline, one that celebrates the great good news that God loves enemies, letting the rain fall on the just and the unjust.

There is another society with a different act of creation and a different DNA. This society is created by the life, death and resurrection of Jesus. Its DNA is marked by gentleness of spirit and active peacemaking. Jesus’ redemptive nonviolent love has already permanently taken care of things.

I believe peace is God’s intention for humanity. I believe that since God has chosen to make peace nonviolently, we are called to do likewise. I believe we show God’s character—we carry God’s DNA—when we are peace-doers.

But that myth of redemptive violence is so strong, so pervasive, so common sense. It’s exciting and oddly comforting. How do we counter it so we can live within the other worldview and find it exciting and comforting and truthful?

Suggestions forPeace Sunday

Suggestions forPeace Sunday

1) Take time to reflect on the myth of redemptive violence. Ask yourself why Gunsmoke, video games and action movies are so appealing. Think about why we accept as common sense an approach that does not stop the cycle of violence.

2) Practise creative ways to stop the cycle of violence in day-to-day things. Then such responses will come more naturally when the big stuff hits.

Read Bible verses that are hard to hear because we think we are being asked to be milquetoasts: “If anyone strikes you on the right cheek…turn the other one also.... And if anyone wants to sue you and take your coat, give him your cloak as well.” Some commentators suggest that the point here is to surprise the opponent by doing something unexpected.

John Roth tells about a time he was given grace to try such an approach. He was travelling late at night in Germany, in a nearly deserted train. An elderly man came on board, dressed in rags and clearly suffering from a mental disability.

Four young men sporting chains and tattoos entered the car and began to taunt the old man. They threw a can of beer in his face, then began kicking and punching him. Roth looked on in horror. He knew he could not sit back and let this helpless old man be beaten.

He prayed: “God, calm my fear. Show me the right thing to do.” Almost before he knew what he was doing, Roth got out of his seat and walked toward the old man.

“Hans,” he called out in his best German. “Hans, how are you? It’s been such a long time since we’ve seen each other.” Slipping between two of the surprised attackers, Roth embraced Hans, helped him to his feet and said, “Come, Hans, sit with me. We have so much to catch up on.”

The old man followed John to the back of the car and responded haltingly to Roth’s questions about his health and family. His attackers were too surprised to know how to react and got off at the next station.

This creative act left the opponents bewildered, and it stopped the cycle. If we live in the spirit of nonviolent love in little things, we will more likely have something to call upon in the great things, something unexpected.

Now, this incident could just as easily have ended with the attackers beating up Roth as well. We don’t know the outcomes of such actions. It’s not an accident that Jesus linked the beatitudes about peace-doing with the one about persecution.

3) Practise Christian humility. Accept that we don’t know all the answers. Humility goes hand in hand with Christian pacifism. We need the humility of respectful dissent, which includes listening carefully to those with other viewpoints, especially those who have been willing to die for their belief in redemptive violence.

We also need what someone has called “eschatological humility.” We don’t necessarily know how history should turn out. God is in control of the ultimate outcome.

We are called to discern God’s will in our daily lives, to be responsible caretakers of God’s creation, to align ourselves with what we can see of God’s movement in history. But ultimately, God is in charge. When we turn to violence, we are saying that we know how history should turn out.

As for redemptive violence, Dorothy Day says: “You just need to look at what the gospel asks, and what war does. The gospel asks that we feed the hungry, give drink to the thirsty, clothe the naked, welcome the homeless, visit the prisoner, and perform works of mercy.

“War does the opposite. It makes my neighbour hungry, thirsty, homeless, a prisoner and sick. The gospel asks us to take up our cross. War asks us to lay the cross of suffering on others.”

The other morning I was startled by the prayer for the day in the Catholic prayerbook I am following. It goes like this: “O God, your son Jesus died giving the message of your love to us. Have mercy on us. Give us the courage to die rather than cause the death of another. Help us to allow his death to mean new life for us and for our world. Never let us stand in the way of your saving grace.” Amen. So be it.

––Sue Steiner

The writer is pastor of Waterloo North Mennonite Church in Ontario and chair of the Christian Formation Council of Mennonite Church Canada. The above is from a sermon she preached on Peace Sunday 2002.

Dramatic story of Lao convert

Winnipeg, Man.

As a new pastor of the Lao Mennonite Church, I pray for wisdom and guidance. I worry about my preaching because I am not a good speaker, but when I feel discouraged, I recall Tym Elias’ words, “Just do your best and leave the rest to the Holy Spirit.”

I began with the goal to have 20 families so that I could feel assured that the Lao Mennonite Church is here to stay. Our church attendance averages 20 people, but I give thanks to my Lord for he has given me four more members who were baptized on October 20 last year. Let me share the story of Somneuk Khousanith.

Khounsanith accepted Christ at the age of 63. Though I have known him a long time, I met him in the name of Christ in 1999. He responded to my invitation and came to our church, just trying to be polite. He said he was too old to change faith. He said that he came to support our good work, to fill one empty chair, lest we would be discouraged and give up.

I told him, “Don’t worry, let the future be between you and Christ.” And then I prayed for him.

A year later, Somneuk was seriously injured in a car accident, breaking both his legs. He was in the hospital for about a year. I visited regularly and prayed for him. One day our church held a special group prayer for his upcoming operation. We formed a circle and sang our favourite song, “What a friend we have in Jesus.”

As we held hands, we all prayed aloud at the same time. Each of us prayed like crazy. As we calmed down, Abe Neufeld, our co-pastor, asked for blessing.

A few days later I visited Somneuk, bringing a cassette tape of the Gospel of Matthew. He told me how happy he was that our group had come to be with him the day before. He described the singing and prayer and how it helped him to feel comforted. He asked to pass along his thanks.

I was ashamed that, as a pastor, I was not the first one to visit him. The following Sunday, I passed his words of thanks to our group. To my surprise, many said they too wanted to visit him and asked for his room number. Each assured me that they hadn’t visited him.

During my next visit to the hospital, I told Khousanith that he had been under the influence of anesthetic which caused him to dream. He argued that I could say what I wanted, but he had seen us there, with his eyes open. He recounted that the doctors and the nurses were working on his leg, and that my group was there, singing and praying. He believed what he saw.

He accepted Christ as his saviour on October 20, 2002.Three weeks before our baptism service, I told him that I would baptize three new believers and wondered if he would consider being one of them.

Without hesitation, he exclaimed, “Yes! That is my birthday.” That day I baptized four. I am so thankful for Khounsanith, Janfong, Liangsy and Lam, because out of these will be the body of our church.

—From report by Onong Prasong

The writer is pastor of Lao Mennonite Church in Winnipeg. Although recent cuts in Mennonite Church Canada mean that he is no longer a full-time leader, he plans to give as much leadership as possible to the congregation.

Copyright for the contents of this page belongs to the Canadian Mennonite. Please seek permission to reprint from the editor .